How WeChat Became the First Chinese App Entered into a Museum Collection

This post comes courtesy of our content partners at TechNode.

A version of WeChat has been acquired by the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) in London to be preserved in perpetuity. This is the first time a social messaging app has been entered into a museum collection. While it may seem an unusual artifact, the app does meet the same criteria used for any item under consideration.

We visited the V&A and spoke to the curators who worked on the acquisition about why WeChat and how they managed it. The idea to add the app came from V&A staff working on the V&A’s gallery within China’s first design museum – the Sea World Culture and Arts Center in Shekou, Shenzhen – seeing first hand the impact WeChat had on users’ daily lives.

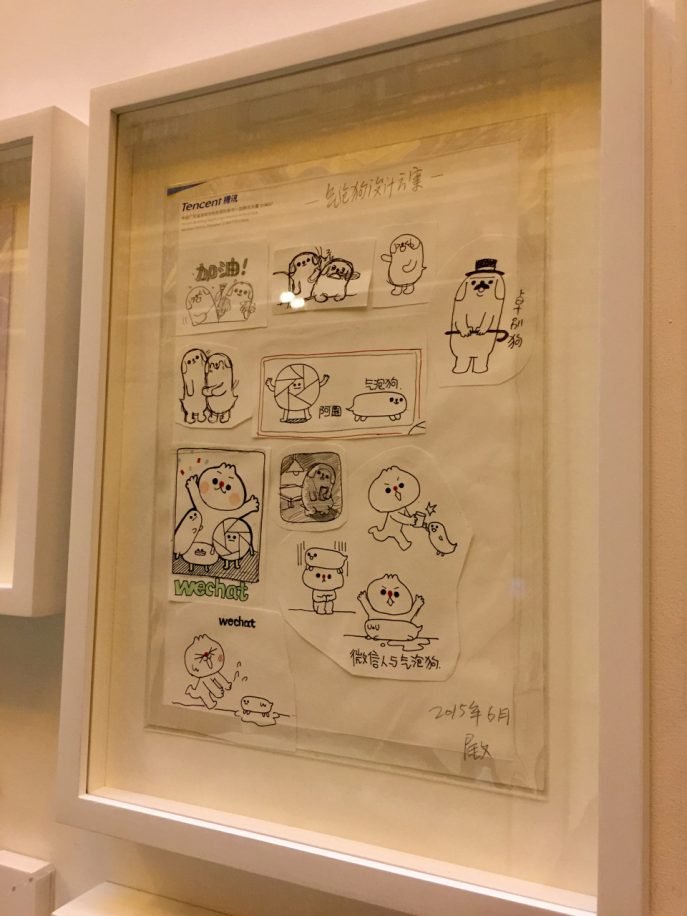

Two and a half years later, in summer 2017, after working with Tencent and museum decision-makers, the release form that completed WeChat’s entry into the archives was finally signed. Two and a half years is a long time in the history of WeChat. Think back to 2015 and 2016 (it was a 2016 version that would be frozen and given to the museum) and many of WeChat’s pioneering features such as voice messaging, stickers, apps-within-an-app had still to be copied by other social apps – WeChat was way ahead of the rest.

The case for acquisition

“WeChat was a forerunner in design innovation in non-textual communication,” explained Corinna Gardner, the V&A’s senior curator of Design and Digital. “It’s an innovator in what we take for granted … WeChat fundamentally changed the way people do things and even its developers at Tencent were amazed at their own power to change regular bodily motions [of lifting one’s phone to one’s mouth to record a voice message],” said Brendan Cormier, lead curator of 20th and 21st-century design for the Shekou Project.

The museum staff noticed the huge rate of adoption and impact on daily life and working life that WeChat had in China, making it the “nerve center of daily life,” according to Gardner. China itself was part of the reasoning. “With its early adoption and an advanced society which is mobile first, WeChat became part of our overall understanding of the use of social media,” said Gardner. “In this respect, WeChat is singular.”

Observing how it had become indispensable to daily life for so many people and its significance as a prime of example of a snapshot of the use of social media in general, the curators had two tasks ahead of them: making a case for its acquisition to the museum and actually acquiring the software in a relevant way.

Context for the collection

When it comes to putting something in a museum for future generations to be able to observe and understand, context is king. “Digital is a new arena where user experience is an integral part of an object. How do you give that object language that is useful in cataloging?” said Gardner on how to create a case for an acquisition, “You have to be able to find ways to monitor an object and the ways you interact with it. The worst is when objects in the collection don’t speak, there’s no context.”

And so the team decided to make a video of people using the app in daily life and simulation of the functions as seen in the app layout. This would capture the app’s usage and therefore its context. “Video enables access to experience the object post-fact,” said Gardner.

The video became part of the gallery display and it is that which you see playing on a Samsung smartphone screen, partly because having WeChat open for visitors to see or use wouldn’t explain it as well as the video context, explained Gardner.

Tricky acquisition and fake profiles

But the team still had to try to get the app itself into the collection. They made contact with the WeChat design department in Guangzhou. WeChat staff were eager to help but also not sure how the app could be handed over in a way that could be preserved: WeChat functionality is based on connection to servers and having contacts to communicate with. There are also privacy issues around storing users’ content and data.

It was the WeChat team who came up with the solution: the closed-off demo version of the app used for getting approvals from Apple. This version does not need to be connected to servers. The V&A asked for the equivalent Android APK which was loaded onto a phone bought specially. And so version 6.5.10 of WeChat sitting on that phone, with a backup of the APK on the museum’s servers for uploading to future devices or emulators, became the acquired object.

But with a few tweaks first. WeChat staff created a fictitious WeChat user called “Star” and came up with a profile, contacts and made up moments. Her invented exploits will be visible to museum-goers forever.

“We had to offline the version,” said Cormier, “You can type on it and post photos, but they don’t get sent.”

Frozen future

The world’s first museum acquisition of a social media app should have been a big moment, and probably would have been had the V&A acquired the likes of Facebook for the collection, said Cormier, “But because it was WeChat we got a lot of shrugs as people don’t know it.” There may be an obligation to now acquire more apps for the collection. Subsequent editions of WeChat may be added to the V&A’s collection in future, possibly in 10-year intervals, but these would be standalone versions and not replacements.

Apps may seem an odd addition to a museum collection, but other similar objects have also been acquired. The MoMA acquired the “@” symbol in 2010 and the US Library of Congress had been collecting every single public tweet from its inception in 2006. Although the library realized last year that it would have to start being more selective as of Jan 1, 2018 due to space limitations and the increased multimedia aspect of Twitter - one of the many difficulties facing curators of the digital age.

The V&A is collaborating once again with Tencent for a video game exhibition that will be on show in London in September 2018.

Photos: Victoria & Albert Museum, TechNode