Author Graeme Shepard Disputes Paul French's Famed Peking Murder Book

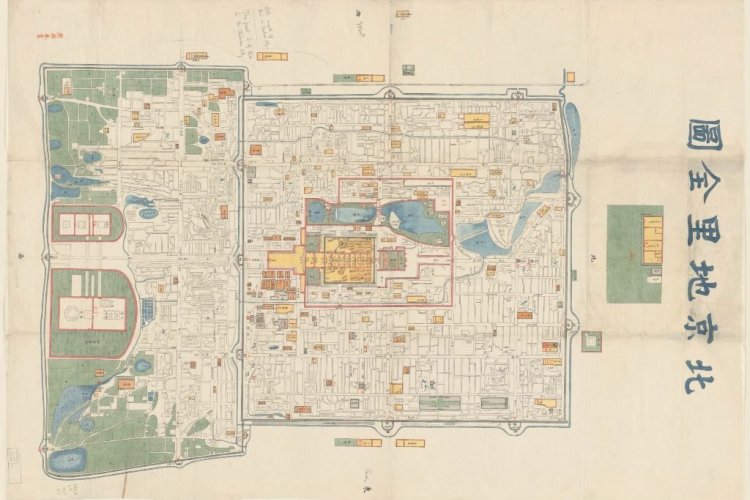

Our fair capital makes Beijingers feel relatively safe. If we decide to disregard the ferocious traffic, of course. In contrast to that, back in the 1930s, Beijing not only went by a different name, Peking, but was also the setting of a notorious murder. The victim, Pamela Werner, was the 19-year-old daughter of a British diplomat, and her story has previously been detailed and brought to a modern audience via Paul French' bestseller Midnight in Peking.

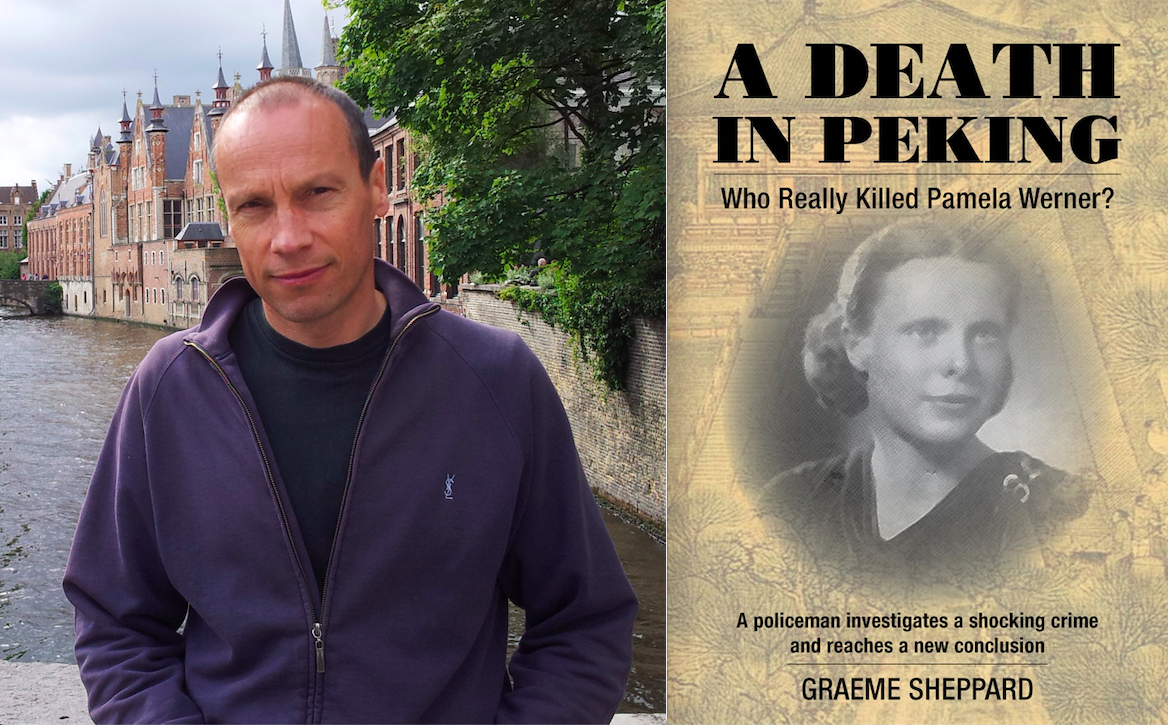

French gave the first comprehensive summary of the puzzling murder and the investigation that followed. However, the facts are of this unsolved murder remain contested to this day, as demonstrated by a book released last month written by a retired British policeman named Graeme Shepard in which he lays out his counter theory. Following an event last week to promote the release of his new book, A Death in Peking: Who Really Killed Pamela Werner, Shepard told the Beijinger that: "Paul French has brought the case to the public eye and he deserves the credit for that. It is a good, enjoyable story, a real page-turner! But it's wrong in its conclusions."

Shepard went on to tell us about his own research and the veracity of his new findings, which come as a direct challenge to the conclusions of its popular predecessor, Midnight in Peking. We will keep the spoilers at bay, but Shepard does divulge who he in fact believes had a hand in Werner's murder some 80 years ago.

You were a police officer in the UK previously. What is your personal relationship with Beijing? You mentioned that you have visited Beijing before but quite briefly.

I just completed a 30-year career as a Metropolitan policeman in London. So my background is in policing, and has nothing to do with China. About five years ago, somebody gave me a copy of Midnight in Peking. My wife's grandfather happened to be a consul in Beijing, so I read it as a result. I don't normally read about crime outside my job. I've been to plenty of awful murder scenes and there is nothing pretty about it. So I picked the book up with some reluctance.

As I was reading through it, I couldn't help but not have my policing helmet on. When I was in London I thought I would have a look at the letters that the book was based on. They outline the murder theories of the father, Edward Werner, who was a retired consul. And I didn't think it was possible that the victim's father had succeeded where the Chinese and British police had failed. I was very skeptical. He was forcibly retired in 1913 from the consular service, due to his behavior. I read them, about 160 pages of a very difficult read. He was a very idiosyncratic person, and it was obvious to me that they were in no way objective. They were a product of a very strange mind. In fact, he has some sort of cryptic personality, to the extent that he found normal relations very difficult.

Did you draw that from the letters?

You could draw that from the letters alone before you read what other people wrote about him. He was described by people who knew him and worked with him in the consular service as completely mad. It's that bad. The letters were just his theories and an awful lot of trashing of everybody involved. All the police were either corrupt or incompetent and everybody he didn't agree with was a sexual deviant.

So how did the idea for your book come around?

I thought: "Well, where do I find more corroboration? There has to be more to this case." Having gotten that far I guess I got hooked, which isn't something I wanted to do.

I managed to speak to some of the children, now in their nineties, that Pamela lived with just prior to her murder. It was pretty much first-hand evidence. I put it all together and I came to a different conclusion, hence the spur for writing a book. The problem with Midnight in Peking is that it follows Werner's theories. Now, this is a man that is described as being maniacally quarrelsome, to quote some people, and even morbidly suspicious.

Listening to what you're putting forward now and remembering what was written in Midnight in Peking, you could draw similar conclusions; that Werner often worked alone and couldn't keep relationships.

Right, the other thing is that he decided on his subjects and then was looking for evidence. It's putting the cart before the horse. Instead of seeing where the evidence led he decided he didn't like the x amount of people and then went about finding suspects. Then he compromised things further by paying agents to find evidence for him. If you go to the street and pay someone enough to find evidence, they come up with what you want. And that's what happened.

The investigation was over by the summer of 1937 when there was a verdict of a "murder by persons unknown." Very shortly after that, it became impossible for the British police to work further on the case, because of the warfare all across China when the Japanese became increasingly antagonistic towards the British.

One of the more exciting things I found in the national archive, in the same place, was a contribution made by Sir Edmund Backhouse. He was a very strange character, and makes Werner look quite straightforward. Backhouse was a sinologist, a linguist, who'd been in China since the 1890s and was exposed as a serious fraudster. Everything he did was somehow related to fraud. A year after the murder he wrote a contribution saying what he had heard from the Japanese. He claimed that the Japanese had murdered Pamela in revenge of a murder of a Japanese soldier by the British. So he had his own murder theory.

Your book is very different in that you gather evidence from side stories and different sources, rather than basing it on one storyline. How were you able to filter through what was relevant to your story?

When you are doing an investigation you have to take in everything that you can find. Instead of focusing on what you want to hear and see, and ignoring everything else, you have to just gather absolutely everything that is available. Now there is an awful lot written about Peking at that time. If you are trying to solve a crime, which, in a sense, we are trying to do, you can't ignore anything. In doing that you come across rumors and plain nonsense. So the difficulty now is deciding what is rumor and nonsense and what is actually something of substance.

In the end, we have eight suspects and the ninth one, that I put forth as the most likely one. He is mentioned just in passing in Midnight in Peking.

How about Werner's letters in your book?

Werner, even though you can't believe a word a man says without corroboration, is very useful when he disagrees with somebody. He then gives the other person's point of view and explains why that's nonsense.

Werner was corresponding with the chief of the police, Richard Dennis, and the chief was convinced with his theory and wouldn't budge. He was sure it was, in fact, a Chinese student. Pamela had spent the previous four years in Tianjin and she'd been moved there specifically because Werner was unhappy about this Chinese boy meeting her outside of school. That student actually got his nose punched by Werner, four or five years before the murder. Then he sent Pamela off to grammar school.

So Dennis was saying it was the Chinese student who was responsible?

Yes, and Werner refused to believe it. He mentions it in his letters and in doing so, he very usefully tells exactly what Dennis has told him. Examining what we have, the simplest equation is the one to go for. And the one that is usually correct.

All I do in the book is look at all those suspects and assign them the percentage of probability. We can't have conclusive evidence, we are not putting anyone on trial here. Some get one percent or less, but one gets 50 percent probability. That's how strong I feel about it. There is no reason to believe that it was more than one person committing the crime.

All Werner's suspects were living in Beijing, carrying on with their lives for years after the crime. The community was so small it would have made your life impossible if you were actually guilty of the crime. The main suspect I put forth disappears afterward.

I am not saying my book is the final word, there could be more evidence to be found somewhere in the world. But I suspect that it would only put more meat on the bone. I doubt it will turn up another suspect.

You can find A Death In Peking: Who Really Killed Pamela Werner on the stalls of The Bookworm and draw your own conclusions.

More by this author here.

Email: tautviledaugelaite@thebeijinger.com

Images: Daily Mail, Publishing Push, Earnshaw Books

![[NR] Forbidden City Book Photo by Haiwei Hu/Getty Images. All Rights Reserved.](https://www.thebeijinger.com/sites/default/files/styles/blog_list_image/public/thebeijinger/blog-images/265699/5_c_haiwei_hu_getty.jpg)