Weekend Walk: Dungeons, Dragons, Warriors, and Princesses

Who needs Dirty Box HBO or your local RPG group to find fantasy elements in Beijing. Warriors, princesses, doomed poets, dragons, and dungeons are as close as a metro ride to Dongcheng.

Our walk starts at Beixinqiao Zhan. Yes, that is the official “foreign language” name of 北新桥站. Why? Don’t know. If you can read the Chinese, spelling out “Z-H-A-N” in pinyin seems unnecessary, while folks who can’t read Chinese aren’t going to know intuitively that 站 means “station” even if they have a pronunciation crib.

Nevertheless, The Metro Stop, formerly known as Beixinqiao Station, has received a major upgrade this year as a terminus for the Airport Express. Now travelers arriving at PEK with a severe craving for spicy crayfish can skip the cab line and get a direct train to Guijie.

But there’s more to the neighborhood than copycat restaurants and language microaggressions. There’s also a dragon biding its time in a deep well somewhere under the streets. There are several versions of this legend, but the most common is that when the Ming Dynasty wished to rebuild their capital on the site of present-day Beijing, there was a dragon already in residence in the area who took issue with this new arrangement.

But the dragon didn't threaten to raze the city, as Chinese dragons don't breathe fire. Instead, he threatened to use his mastery of the wind and water to perpetually flood the new capital. Hearing this, the emperor dispatched Liu Ji, one of his top officials and urban planners, to try and stop the dragon’s scheme.

Liu Ji traced the source of the dragon’s flood to an “Eye of the Sea,” one of several mystical wells which dotted the landscape. Liu Ji – calling in some favors with a few deities and a couple of legendary heroes – convinced the dragon to descend into the Eye of the Sea and remain there.

In China, you don’t slay a dragon.You set up a meeting and engage in a frank exchange of views. To preserve the dragon’s peace and quiet, Liu Ji offered to build a bridge over the portal, and the dragon agreed to remain there until the bridge became old and unusable.

Liu Ji, an early adopter of language microaggression in place names, dubbed the bridge the “New North Bridge,” tricking the dragon into thinking that no matter how much time passed, the bridge over his home/prison was always “new.” Hence Bei Xin Qiao. There is a replica of the bridge in the small park just to the west of Beixinqiao Zhan, Exit D.

From Beixinqiao, head south along Dongsi Beidajie about 400 meters. On the west side of the street is the entrance to Xiguan Hutong, once home to the writer Tian Han (1898-1968). Tian Han was an influential playwright notable for incorporating elements of the international stage, including spoken-word dramas and plays, which competed with traditional opera for the attention of theatergoers in Republican-era China.

Later he wrote the lyrics to a rousing little ditty that became popular after being featured in the 1934 patriotic film Children of Troubled Times. That song, March of the Volunteers, would eventually gain even greater fame as the national anthem of the People’s Republic of China. (Didn’t help Tian Han much in the end. I don’t want to hurt the feelings of anyone, but let’s just say the late 1960s were not a particularly good time to be an older artist or intellectual in Beijing, even if you were "the dude who wrote the National Anthem.”)

At the west end of Xiguan Hutong is a small (sanitized) memorial to Tian Han. If you walk into the hutong about 140 meters, you can see where the author lived until 1966. The courtyard has one of the last original gates on the hutong and is worth a look.

Head back to Dongsi Beidajie and continue south. The next major intersection is with Zhang Zizhong Road. There aren’t many streets (or subway stops) in Beijing named for modern historical figures and fewer still named for Kuomintang officers, but General Zhang was a hero of the Sino-Japanese War and was killed-in-action fighting against the Japanese Imperial Army at the Battle of Yichang in 1940.

The large Western-style compound on the northwest corner of the intersection is the former headquarters of warlord and politician Duan Qirui (1865-1936). Duan was the commander of the Beiyang Army, one of the major military forces in North China in the years following the end of the Qing Dynasty.

With his troops behind him, Duan was one of the players in a decade-long struggle for territory and power in the vacuum left by the end of Qing rule and the implosion of the Republican government following the death of Duan’s mentor, the president-dictator-wannabe monarch Yuan Shikai. When Duan finally seized power as “Chief Executive” of the Republic in 1924, this compound served as his residence and seat of government.

While the compound is officially off-limits to visitors (most of the buildings are managed by Renmin University), in the evenings, Arch Cocktail Bar serves up high-class libations in a secluded corner of the complex. It’s worth looking for.

In front of the gateway is a memorial to the victims of the March 18 massacre. On that date in 1926, students demonstrating against the government of Duan Qirui were gunned down by soldiers on this spot.

Walk east along Zhang Zizhonglu. Just past the Duan Qirui buildings is a sign marking the former residence of Ouyang Yuqian (1889-1962). Ouyang Yuqian was an important playwright who, along with Tian Han, helped popularize spoken-word dramas. Ouyang Yuqian served as the first president of the Central Academy of Drama, located on nearby Nanlguoguxiang, from 1950 until his death in 1962.

His house is a fascinating mix of Western and Chinese style set in a Beijing courtyard. Unfortunately, quite a few folks have poked their heads into the yard to take pictures of Ouyang Yuqian’s house, and the current residents have posted signs discouraging future visitors.

Next door is a hotel set in the former palace of Princess Hejing (和敬 Héjìng 1731-1792), not to be confused with her sister, Princess Hejing (和靜 Héjìng 1756-1792). Isn’t Chinese history fun?

The elder Princess was a favorite of her father, the Qianlong Emperor. While he was perfectly okay with marrying her off to a Mongolian prince to help shore up a political alliance, he was less cool with her moving to the steppe, and the happy couple lived here instead.

The closed red gate at #23 Zhangzizhong Road leads to another famous former residence. In the 1920s, it was the home of Koo Vi Kyuin (顧維鈞 Gù Wéijūn) who is better known in the West as Wellington Koo (1888-1985). Koo had a long career as a diplomat, representing China at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and as ambassador in the United States and the United Kingdom.

He was also a participant in the founding of the League of Nations and served on the International Court of Justice at The Hague. In 1925, Koo was tending to his very sick friend, Sun Yat-sen.

The revolutionary leader had traveled to Beijing to negotiate with Duan Qirui and the other warlords even though Sun was in the advanced stages of cancer. After doctors informed Sun that they could do nothing more, Sun returned to Koo’s home, where he passed away on Mar 12, 1925.

Finally, walk to the next intersection (Jiaodaokou Nandajie) and turn left. Head north for about 200 meters to Fuxue Hutong, on the western side of the street. Enter Fuxue Hutong and walk about 150 meters until you see the sizeable traditional compound on the north side of the road. This is the former academy for Shuntian Prefecture (one of the historical administrative divisions of the city).

The academy was where the sons of the elite would receive instruction and study tips on how to pass through the gauntlet of exams that stood between them and a successful career. Part of the academy is now a primary school where the children of Beijing receive instruction and study tips on., etc., etc. While the site dates to the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), only a couple of structures are from the imperial era and were part of an 18th-century renovation.

Nestled between the academy and the school is the entrance to a shrine honoring the Song Dynasty general Wen Tianxiang (1236-1283). He was a politician and poet serving in the Song court but was forced into military duty against the Mongols. He turned out to be a decent general but was eventually captured by the Khan’s forces.

According to local legend, Wen was imprisoned in this courtyard while the Mongols attempted to get him to switch sides. Wen refused, and the Mongols executed him. The shrine honors Wen as a paragon of filiality and patriotism. You can visit the shrine by checking in with the office inside the gate and paying the 5 RMB admission fee.

About the Author

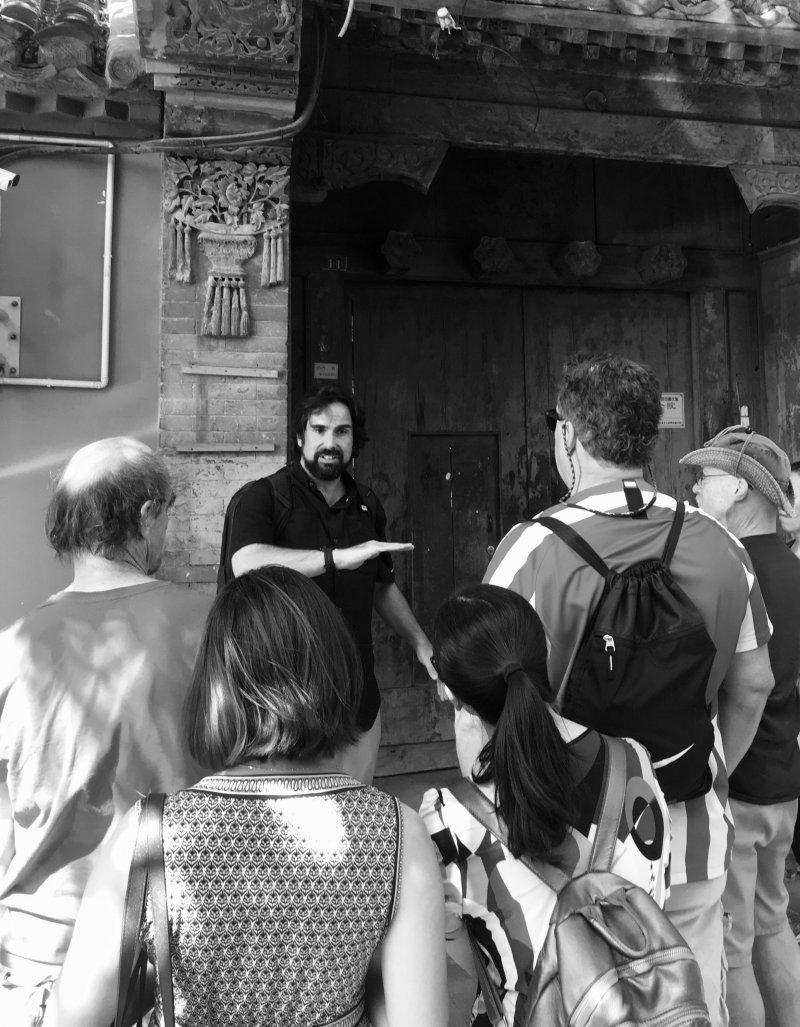

Jeremiah Jenne earned his Ph.D. in Chinese history from the University of California, Davis, and taught Late Imperial and Modern China for over 15 years. He has lived in Beijing for nearly two decades and is the proprietor of Beijing by Foot, organizing history education programs and walking tours of the city including deeper dives into the route and sites described here.

READ: Weekend Walk: The Basics of the Forbidden City

Images: Wikipedia, Jeremiah Jenne, Bespoke Travel