Q&A With Nobel Peace Prize Photographer Sim Chi Yin Ahead of Mar 16 Bookworm Talk

Sim Chi Yin has faced down a nuclear missile, literally. It was for a very prestigious assignment – the lauded Singaporean photographer and former China correspondent for The Straits Times had been commissioned to make a photo exhibit for the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize winner, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). For the project, Sim traversed 6,000 kilometers along the North Korea-China border and through six states in America to visit nuclear silos and other such sites. While gazing up at one particular Cold War-era silo in America, Sim realized that an exterior shot would pale in comparison to an overhead photo, so that the missile would face the viewer, dead on.

In order to achieve that, Sim recalls being "put in a safety harness and lowered into a silo to photograph it from the top," she says, ahead of her Mar 16 talk about the Nobel Peace Prize exhibit. She adds, with powerful understatement: "Those overhead pictures are probably the most dramatic ones in the project."

Below, the daring and endlessly resourceful photographer tells us more about the pressures of working on that prestigious project, how humbling it can be to visit these towering nuclear weapons facilities in person, and more.

What can people expect from your talk at the Bookworm?

I'll be sharing the project that I photographed on commission for the Nobel Peace Prize in a slideshow.

How did you manage to land such a prestigious project?

I basically just got an email from the Nobel Peace Center last year, asking if I would like to be the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize photographer. They had seen my work over the years, and they decided to approach me this year. This is an annual exhibition commission, they've done it annually for years now. According to the Nobel Peace Center's curator and exhibition director, this is the first time they commissioned an Asian photographer for the project. It's a pretty prestigious commission, so I said yes.

What were some of the challenges you faced?

At the time that I accepted, we had no idea who or what the Nobel Peace Prize winner was going to be. The laureates are announced on Oct 6 every year, then on Dec 10 is the Nobel Peace ceremony in Oslo. That means this exhibit had to be created before then, so I only had about two months flat, from research to shooting to installing and opening the show. It's a very intense kind of commission and this is what we had to work with. The opening is meant to coincide with the anniversary of Alfred Nobel's death, Dec 10. So when people complained to me about it being a rush, and asking us to move the date, we had to firmly tell them no.

I didn't know who the subject would be and speculated maybe Angela Merkel or the Pope. In the case of it being a person, it would just be reportage, a week in the life of this person. Then I found out it was ICAN, which is an international civil society group with branches around the world. And the organization itself is just people in an office doing their work.

How did you go about making the photos more eye-catching, then?

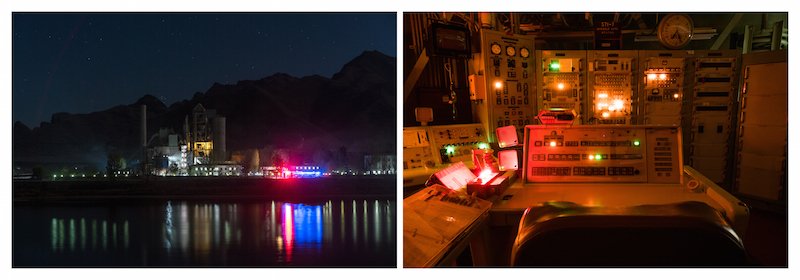

I went for something that might be called "conceptual documentary" in today's language. It consists of paired pictures, one half being from North Korea and the other half from the US. And all these landscape pictures have something to do with nuclear-related sites and scenes.

Then it was a matter of finding places to photograph. A lot of research was involved, a lot of speaking to academics and veteran nuclear activists and campaigners, and looking at satellite maps. We traveled 6,000 kilometers by road, not including flying, to reach these places. So I visited six states in the US and also most of the China-North Korea border.

What were some of the most memorable moments from those shoots and all that traveling?

In the US we went into Cold War-era nuclear silos. At one of them, I was put in a safety harness and lowered into a silo to photograph a missile. Those pictures are probably the most dramatic.

What was that like?

The US is very safety conscious. So we had to take out a huge liability insurance to even be able to go inside. I got in the harness to photograph it from the top because I didn't think it would make sense to shoot it from the side – you would only get a fractional view. What I wanted was a view from the top. So I was lowered slightly onto a platform. I climbed down maybe five meters. Then I was able to balance myself on the edge of a ledge to lean over and photograph the top of a missile. It was the Minuteman II missile, which is no longer in use, though the Minuteman III is the missile of choice in service at the moment. So all of these things that I photographing in America are from the Cold War era. But what struck me is that this issue is a very contemporary one. I mean, it's in the news today. North Korea is talking about being willing to stop tests and denuclearize. It sounds like it's great news, but we don't really know.

There was another very memorable shoot in the middle of nowhere in rural North Dakota. I was photographing what resembled a pyramid. When you see the picture, you see one of its four faces. And on each face, there's this eyeball-like circle that's just humongous. It was a very distinctive structure, and it was just sitting there in this remote area.

What did that structure turn out to be?

It was a radar facility built in the early '70s and was designed to spot and shoot down Soviet missiles coming down over the North Pole. When we first discovered it we were like: "What the hell is that thing?" And then we were able to get inside it, and get behind the eyeball circles on its sides, and climb all over it, go into its basement. It's been abandoned since the mid-70's, so everything was rusty, and there was water all over the ground. It was like something out of Star Trek, except very rusty and abandoned. It was just mind-boggling. It very much made me ponder the amount of resources and human genius that has been put toward nuclear weapons, and all its related industries.

In the exhibition, in Oslo, the photos displayed are quite large: four-meters wide. So it's quite bold, and you stand in front of these landscapes and wonder "What am I confronting?" My intention was to help people suspend their sense of place so that when they looked at the pairs of images, they might not be able to tell which picture is from the North Korean border and which is from the US. Once you look at the images, you'll really be surprised by how many parallels I found – be they visual, historical, and more. It also demonstrates how cyclical history can be. The US was the first country to have and to use nuclear technology as weaponry. And North Korea is the only country in the 21st century to test nuclear weapons.

Some people asked me why I paired the pictures together in this way. I think art and photography can compel you to ask questions, and it can get people to reflect on some of the international issues we live with. So when you look at the images you might not be able to tell which is which and what is what. And then you might think: "How do we decide who gets to have this stuff, these extremely powerful weapons? And who gets to pass moral judgment on whom?" So I'm just trying to ask some of these questions with this project.

Did you get any responses to such questions?

One that was particularly moving was during the opening week. We did a showing for the Hibakusha, which are the people who survived the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They came as a group, and they toured the exhibition, and they were quite struck by how the images were paired. They understood the intention immediately. One person came up to me and said: "Who's to say North Korea is good and American is bad?" But America dropped two bombs on them, so of course, they will say that. Yet, for them to immediately understand what they were seeing, and what the intention was behind the pairings, was quite heartening, really.

Sim Chi Yin will appear at the Bookworm on Mar 16 at 6pm. Entry is RMB 60. For more information, check the entire schedule for the International Literary Festival here.

More stories by this author here.

Email: kylemullin@truerun.com

Twitter: @MulKyle

Instagram: mullin.kyle

Photos: The Wireless, courtesy of Sim Chi Yin