AQI and PM2.5: Origins Founder Liam Bates Explains the Meanings Behind these Terms

This post is sponsored by Origins, a young technology company based in Beijing that develops cutting edge smart devices designed to help people build and sustain a healthy lifestyle.

As if the Capital’s pollution weren’t oppressive enough, it can be equally overwhelming to understand how, exactly, air quality is measured. Those terms, facts and figures can seem as hazy as the pollution itself, but Liam Bates hopes to clear the air with a few simplified explanations. Below the founder of Origins breaks down the significance of a few key AQI related terms, dispels some misconceptions about that air quality index, and describes how some devices take those measurements.

PM2.5’s: Even tinier (and more abundant) than you thought

After years of headline dominance and extensive media scrutiny, nearly all Beijingers have an idea of what PM2.5 is: the “particulate matter” pollutant particles that, according to Cntv, are so fine they “can reach the deepest regions of our lungs; and exposure to [which] is linked to a variety of significant health problems, ranging from aggravated asthma to premature death for people with heart disease …” A term which indeed lives up to its nickname the "Invisible Killer."

Ominous nicknames aside, Bates says many people do not have a full understanding of what the term means. “PM2.5 refers to all particulate matter that has a diameter of less than 2.5 microns. So it’s not just anything that’s PM2.5 in size, but also anything smaller than that,” he explains, adding that many big air quality monitors, like the one at the US Embassy, draw in air samples and are able to monitor pollutants anywhere from 2.5 microns to less 0.1 microns in size (all of which are categorized as PM2.5’s, and all of which are highly harmful).

Relative Readings: American and Chinese AQI’s may not always jibe, but it doesn’t mean they are inaccurate

Bates says a common misconception among Beijing expats is that the Chinese government is skewing its air quality index (AQI) readings. But he goes on to explain why the discrepancy isn’t a matter of deceit, but rather one of differing standards and more realistic expectations.

“A lot of people think the government is lowering the numbers on purpose. But there’s actually a lot of research that shows their numbers are very accurate, that they’ve invested millions of dollars into equipment and training,” Bates explains, adding that the gap in those numbers stems from China’s differing conversion system, adding: “That’s why people that are used to looking at the American AQI see that the Chinese AQI is lower and think: ‘Wait, that’s not right.’”

According to Bates, both the U.S. and Chinese AQI indexes are based on complex measurements of micrograms of pollutant particles per cubic meter; but where the two AQI indexes differ is in their cutoffs for “good” and “mediocre” levels of those particles per cubic meter. The indexes are both designed to simply show 0-50 AQI as being “good,” then 50-100 as “moderate,” and so on – this allows the average person to have a general idea of the air quality without having to scrutinizing more complex micrograms per cubic meter.

As Bates explains: “When the pollutants in the air go above 12 micrograms per cubic meter, the AQI goes over 50 on the US scale, which is an increase from ‘good’ to ‘mediocre.’ Whereas in China, everything under 35 micrograms per cubic meter is ‘good,’ even thought that would be a mediocre day on the US index.”

Bates goes on to say that China’s AQI experts are not blatantly slacking off or being overly complacent – instead, they are attempting to work within the reality of China’s unique environment. He adds: “The US has decided that even a little air pollution is not very good.” His comment coincides with that of the World Health Organization, which says, essentially, that there’s really no such thing as an acceptable level of such pollutants. Its website explains: “Small particulate pollution have health impacts even at very low concentrations – indeed no threshold has been identified below which no damage to health is observed. Therefore, the WHO 2005 guideline limits aimed to achieve the lowest concentrations of PM possible.”

However, Bates says that the PRC’s air quality experts need to reckon with different standards.

“The Chinese index’s version of AQI 50 allows for a lot more pollution than the American index. I personally think China’s is too relaxed, but the reason they do this is so that they can have an interim target, one which they can actually achieve, and if they hit that target they can make standards stricter later. But if they use the higher American standard, then Beijing would never have had a ‘good’ AQI day under 50. There’d be only a very scant few days like that over the past few years, which is really depressing. For now, they see this as a stepping stone.”

Breaking it Down: How China’s AQI readings can sometimes be more accurate than the US version

While China’s AQI standards may be too lax in Bates’ opinion, he also says that the PRC’s index has some unique advantages. Chief among those attributes is the fact that the Chinese government monitors a variety of pollutants like ozone, sulphur dioxide and carbon monoxide, instead of focusing solely on PM2.5’s.

“The U.S. embassy only measures PM2.5’s, nothing else,” Bates says, adding that the PRC, meanwhile, measures “whichever pollutant is the highest – be it ozone, sulphur dioxide, PM2.5’s or others – and bases the AQI on that. He adds: “So there will be days when the PM.25 levels are not high, but the Chinese AQI is high, and that could be because there’s a harmful level of ozone in the air that day. In a way, the Chinese index could potentially give more information than the US embassy and be even more accurate.”

PM2.5 concentration: The raw, unfiltered info

But what, exactly, are we talking about when considering “micrograms per cubic meter?” This measurement is the baseline used to precisely determine how heavily concentrated PM2.5’s are in the air, before those figures are simplified on AQI scales for public consumption.

These micrograms per cubic meter figures are obtained at the US Embassy in Beijing, along with other air quality gauges around the world, with “Beta Attenuation Monitors” (BAM). According to EPA.gov these massive (and highly expensive) devices draw in samples of air through a sample nozzle and then emit beta rays on the air once it’s inside the machine. Those rays are attenuated (i.e. weakened) by pollutants in the air, helping the device read how concentrated the pollutant particles are.

“It’s super raw data that should be the same, regardless of what country you’re in or what calculation system you’re using,” Bates says of the ensuing micrograms per cubic meter measurement that the BAM devices display once their beta rays finish highlighting the pollutants. He adds that this measurement is, in essence, the most reliable air quality reading, adding: “If you want to know what’s really happening with your air quality, then you should look at the micrograms per cubic meter, not the AQI.”

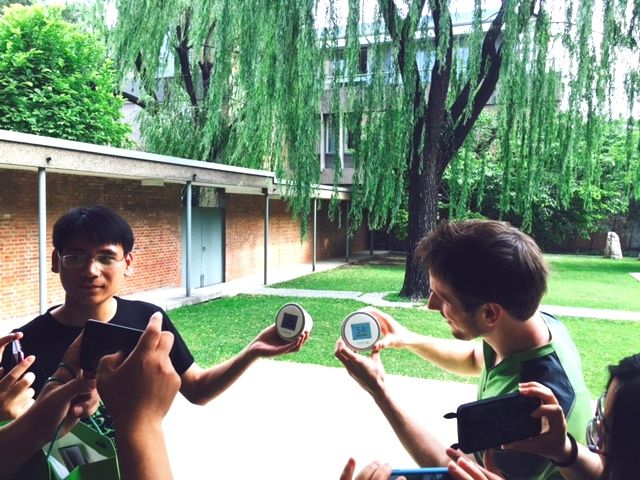

This factor plays into what Bates says is the “coolest” feature of the Laser Egg, Origins’ palm-sized, affordable air quality monitor that has just been released for purchase online and at their Beixinqiao office. “We give you the choice to change between Chinese AQI, American AQI and pollution concentration in micrograms per cubic meter.”

The Laser Egg costs RMB 379 and is now available for pre-order via credit card on Paypal or Jingdong at this link.

Related stories :

Comments

New comments are displayed first.Comments

![]() Origins

Submitted by Guest on Wed, 06/17/2015 - 00:59 Permalink

Origins

Submitted by Guest on Wed, 06/17/2015 - 00:59 Permalink

Re: AQI and PM2.5: Origins Founder Liam Bates Explains the...

You are very right, nanoparticles are particularly harmful to human health, and are often misrepresented by ug/m3 readings. The problem is that even A LOT of nano/ultrafine particles weigh very very little, so the numbers will appear similar or even the same regardless of different quantities.

The Laser Egg measures down to 0.3 micrometres and provides actual particle count, not just ug/m3 which allows for much clearer information. Although this is not in the very very small nanometer range, it's not bad. If you want to measure nanometre particles, unfortunately a big piece of very expensive equipment is still required.

Sand and salt will often be larger than PM2.5, and be in the PM10 rnage. You are right though, a better way of measuring and recording nanoparticles would be great! We'll keep working on it

![]() jumpinship

Submitted by Guest on Mon, 06/15/2015 - 12:34 Permalink

jumpinship

Submitted by Guest on Mon, 06/15/2015 - 12:34 Permalink

Re: AQI and PM2.5: Origins Founder Liam Bates Explains the...

Glad to see the price tag on this device, but it seems Liam might have repackaged an idea from elsewhere.

For an alternative that collects more information I would deffinitely recommend the Air Quality Egg. It's been around for a while and the've been used by people worldwide. Also, it seems they're coming out with a new version, too! Anyway, always good to have options in the this trending pollution sollution market.

Validate your mobile phone number to post comments.