Story of the 'Jing: When Beijing's Most Famous Sites Opened Their Doors to the Public

In Story of the 'Jing, we look at the history and tales of our fair city and how they inform the capital as we know it today.

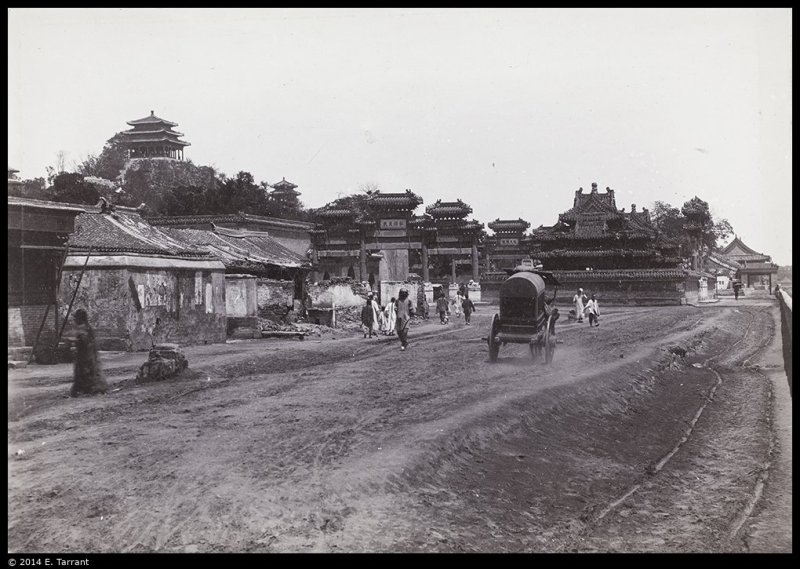

Beijing in the 21st century does not lack historical sites worthy of an afternoon’s exploration. The current iteration of China’s capital dates back at least 600 years, or 700, depending on your opinion of Mongolian cultural and aesthetic contributions to urban planning. Since many of the most popular contemporary tourist attractions were those once exclusively controlled by the imperial court, despite their antiquity, it’s only been in the last century or so that ordinary people (never mind random foreigners) had access to the city’s historic parks and palaces.

The agreement that led to the abdication of the last emperor of the Qing Dynasty on Feb 12, 1912, included a caveat that the boy monarch could continue residing in at least part of his family’s old Forbidden City. While Puyi lived in the back hall of the palace, distinguished visitors and those with money for a ticket could visit a “Gallery of Imperial Antiques,” which opened in 1914. A decade later, the warlord Feng Yuxiang evicted the unfortunate former emperor and his family from the palace grounds. On Oct 10, 1925, a grand ceremony inaugurating the new Palace Museum was held in front of the Gate of Heavenly Purity, once the dividing line between the outer court and the private inner realm of the imperial family. The Palace Museum at the Forbidden City celebrates its centennial in 2025, and plans are already underway for a series of special exhibitions marking the occasion.

Other sites in the old Imperial City, including many of the gardens surrounding the palace, were also opened to the public following the end of the dynasty. The Altar to Grain and Soil, located southwest of the Forbidden City, was opened as “Central Park” in 1914, one of the first former imperial sites to become a fully public park. In 1928, the name was changed to “Zhongshan Park” to honor revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen (commonly referred to in Mandarin as Sun Zhongshan) who died in Beijing in 1925. Opposite Zhongshan Park on the other side of Tiananmen Gate, the former Ancestral Temple complex opened in 1924 as “Peace Park” before receiving its current name, “The Beijing Working People’s Cultural Palace,” on May 1, 1950.

Access to Beihai Park was more limited. It was converted into a park in 1925 but was often closed to the public depending on the needs of the municipal and, later, the central government. It was re-opened in 1978 and has remained one of the city’s most visited former imperial gardens. Nearby Jingshan Park, famous for its 360-degree views of the city, was opened as a park in 1928 under the management of the then recently established Palace Museum.

Without an emperor, there was little need to maintain the altars and other ritual spaces of the Temple of Heaven. Yuan Shikai, provisional president of the Republic of China but with an eye toward a more permanent position, carried out the last imperial sacrifices at the Temple of Heaven in 1913. Yuan died in 1916, his imperial ambitions in tatters, and the Temple of Heaven opened to the public in 1918.

The Summer Palace is another former imperial space that has since become a popular tourist attraction. The gardens, known in Chinese as Yiheyuan, were rebuilt in the 19th Century after being destroyed by the Anglo-French Expedition of 1860 at the conclusion of the Second Opium War. Following the end of the Qing Dynasty, there had been a plan to eventually relocate the last emperor from the Forbidden City to the Summer Palace once suitable renovations had been made. In 1914, the imperial family authorized the opening of the Summer Palace to visitors, hoping ticket sales could defray some of the maintenance and reconstruction costs. Puyi’s eviction from the Forbidden City also meant the end of the former imperial family’s control of the Summer Palace. The Beijing Municipal Government converted the space into a public park in 1924.

While many sites in Beijing opened to the public during the Republican period, few remained consistently accessible throughout the 20th Century. There were long periods — especially in the 1960s and 1970s — when former historic spaces were either closed for protection or repurposed for modern uses, including as police stations, storage facilities, factories, schools, and community centers. Prince Gong’s Mansion, near Qianhai, was used partly as a school, a barracks, and an air conditioner factory before getting a total makeover and welcoming the public beginning in 1996. The Confucian Temple and Imperial Academy housed the collection of the Beijing Capital Museum until 2006. Some form or another of the Dongyue Temple has stood in its current location along Chaoyangmen Outer Street for over 700 years, but in the 20th Century, the site was handed over to a number of official (and unofficial) offices and organizations before what was left of the complex received a much-needed facelift and began re-admitting visitors in 1999 (it is currently closed for another set of renovations).

It’s easy to take for granted the access that we have to Beijing’s past or the care with which many of these sites are currently being maintained, preserved, renovated, and rebuilt. While many historic places no longer exist (or exist as they once did in the imperial period), the efforts to open Beijing’s history to the world have made it possible for residents and visitors to experience a little bit of the grandeur and majesty of the city’s imperial past.

-------

About the author:

Jeremiah Jenne earned his Ph.D. in Chinese history from the University of California, Davis, and taught Late Imperial and Modern China for over 15 years. He has lived in Beijing for nearly two decades and is the proprietor of Beijing by Foot, organizing history education programs and walking tours of the city.

READ: Story of the 'Jing: What's the Deal With the Old Red Gate on Ghost Street?

Images: University of Bristol Historical Photographs of China