Story of the 'Jing: A History of Commerce at Longfusi

The area around the former 隆福寺 Longfusi (Temple of Abundant Blessings) is a popular place to get some of Beijing’s best Pho at Susu or grab a pint (or four) at Jing-A, but the neighborhood historically is no stranger to commerce.

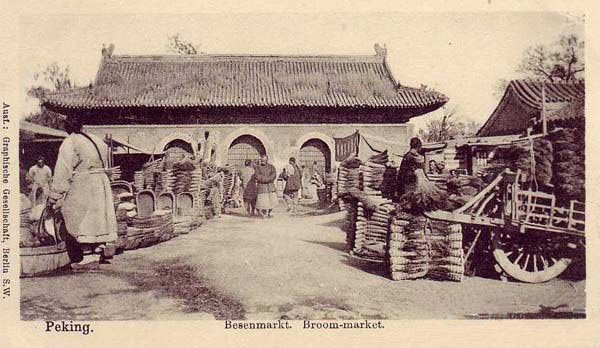

The Longfusi complex was built in 1452 and underwent a significant renovation in 1723, but a fire destroyed most of the main structures in 1901. By the early 20th century, the two dozen or so monks who remained in residence subsisted mainly on the money they earned by hosting one of the city’s largest temple markets. These monthly fairs, with vendors setting up stalls, blankets, and carts inside and outside the temple, met on the 9th and 10th day of every month.

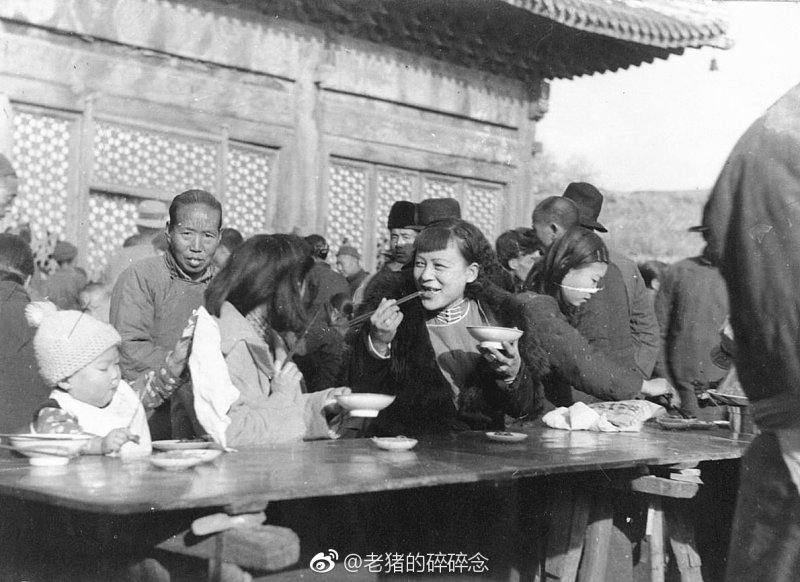

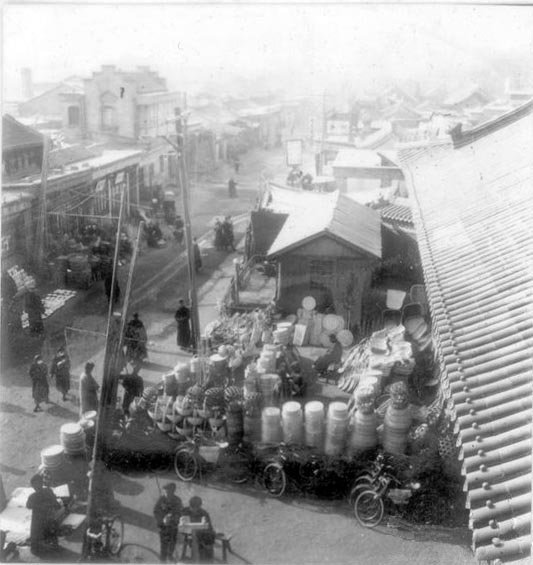

Regular temple fairs were common in old Beijing. Clothes, food (lots of food), antiques (genuine and otherwise), jade and jewelry (ditto), flowers and birds, insects and fish, silk, pearls, and household goods of all kinds were on offer. It was a mobile shopping mall, as vendors traveled from temple to temple, market to market, according to a fixed schedule. While the temple fair at Longfusi was a monthly affair, vendors would also gather on religious festival days and, of course, for the annual bacchanal Temple Fair to celebrate the Lunar New Year.

By the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the monthly market at Longfusi was one of the largest and liveliest in the city, rivaled only by the one held at 护国寺 Huguosi (Defending the Nation Temple) west of Houhai. The two markets were so famous that many Beijingers referred to Longfusi, in Dongcheng, as the “East Temple” and its Xicheng counterpart as the “West Temple.”

The Longfusi Temple Market was not only a Beijing mainstay but had an international reputation. The official delegations dispatched from the Korean Peninsula to meet with the Ming and Qing emperors frequently took advantage of their time in the Chinese capital to do a little shopping. Korean envoys often patronized the market at Longfusi and Huguosi, as well as the antique markets at Liulichang.

A survey done in the early 20th century noted that even with the rise of “modern” commercial spaces and stores in places like Dong’an Market on Wangfujing or the Dashilar shopping street, the temple fair at Longfusi remained a major draw for sellers and shoppers. The surveyers counted over 480 market stalls set up inside the old temple courtyards, with an equivalent number spilling out into the surrounding streets. In addition, there were hundreds of roving peddlers, street performers, and wandering purveyors of drinks and snacks.

The Second Sino-Japanese War and the Japanese occupation of Beijing in 1937, followed by hyperinflation and political instability in the city during the Civil War from 1945-1949, contributed to the market's decline. After the founding of the PRC, the Peking City Vendor Bureau was established to regulate street commerce, with the last traditional temple market at Longfusi being held in 1950. To make room for the new “Dongsi People’s Market,” several sections of Longfusi were demolished in the 1950s. The rest of the temple complex succumbed to not-so-benign neglect. A cinema and theater were built where temple buildings once stood. What was left of the temple was demolished after the Tangshan Earthquake severely damaged the few remaining structures.

Even though the temple ceased to exist, the market persisted into the 21st century. Until the final closure in 2016, hundreds of vendors gathered each morning in the area around the former temple site. It could be chaotic and messy (each day, sanitation workers had their hands and buckets full with all of the litter and debris left behind), but local residents, especially in the Dongsi neighborhood, relied on the market for less expensive food options and to buy goods at significantly lower prices than the shopping malls and supermarkets increasingly favored by city authorities.

In August 2019, the Longfu Cultural Center officially opened on the site of the former morning market as a shopping and dining destination in Dongcheng. While the courtyard has proven popular with ex-pats and many local Beijingers, some in the neighborhood mourn the loss of their beloved market. Certainly, Beijing’s street vendors and temple fairs were an essential part of the city’s intangible cultural heritage. Perhaps in the future, the space between the microbreweries and museums at Longfusi could be opened to pop-up vendors, temporary fairs, buskers, and food carts as an homage to one of Beijing’s liveliest former commercial spaces.

About the Author

Jeremiah Jenne earned his Ph.D. in Chinese history from the University of California, Davis, and taught Late Imperial and Modern China for over 15 years. He has lived in Beijing for nearly two decades and is the proprietor of Beijing by Foot, organizing history education programs and walking tours of the city, including deeper dives into the sites described here.

READ: Eunuchs in Beijing: The Bad and the Misunderstood

Images: Wikicommons, The Beijinger, 老猪的碎碎念