Confucius Says Ease Off the New Year's Resolutions, According to Author Edward Slingerland

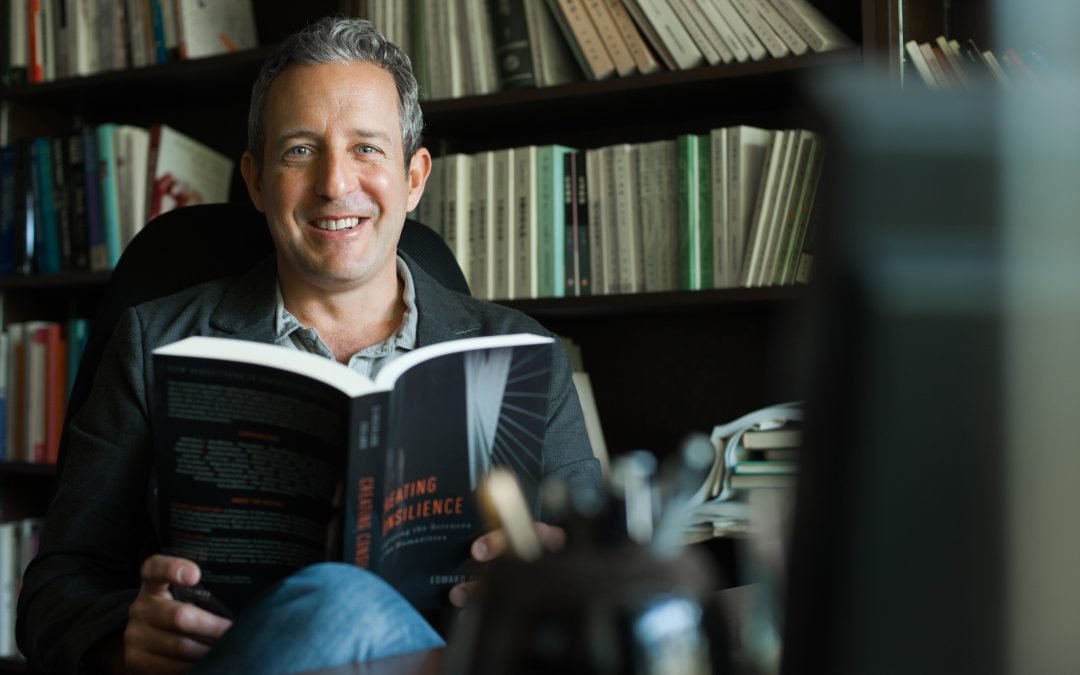

Our bustling modern Beijing lives could use a bit of good old-fashioned Daoist chill, at least according to Edward Slingerland. The author and academic argues that ancient Chinese culture espoused a certain strategic mellowness that is the key to happiness and success. He detailed all that and more in his book Trying Not To Try: Ancient China, Modern Science and the Power of Spontaneity, which was first published by Crown in 2014.

A Mandarin edition of Trying Not to Try is now being launched in China, prompting Slingerland (currently a professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada) to stop by The Bookworm on Jan 10 for a well-timed talk that will hopefully help anyone struggling to keep their New Year's resolutions to cut themselves some slack.

Below, he speaks to us about topics as varied as the virtues of maxin' and relaxin' Daoist and Confucian-style, the modern psychology that now fortifies those aged notions, how athletes adopted this approach to avoid "choking under pressure," and more.

Do you think it would be especially good for Beijingers to come to this event and pick up a copy of Trying Not to Try, seeing as it’s New Year resolution season?

One of the main themes of the book is the power and importance of spontaneity and relaxation when it comes not just to personal well-being but also success. We’re taught that we need to strive and struggle for everything, but there are many goods in life – happiness, creativity, charisma – that cannot be realized by direct striving. Actually, actively trying to get them makes it less likely you will. This is an important message for anyone in modern, urban society, but probably in huge mega-cities like Beijing most of all.

Tell us about a time in the past where you were putting forth such considerable effort to no avail, and how the lessons of this book would have helped you.

The one example I give in the book is from when I was single and dating. I would go out to bars or parties actively trying to meet someone and was wildly unsuccessful. Finally, I gave up and decided to just be happy hanging out with my friends and doing my work, and suddenly it was raining women – people were practically chasing me down the street and accosting me in cafés. Having had a better grasp on the link between spontaneity and charisma that I explore in the book would have been helpful! I wasn’t far enough along in my study of Chinese thought at the time ...

Speaking of which – your book has been praised for tying "together insights from early Chinese thought and modern psychological research." When did you first begin to realize the overlap between the two?

Since I finished my Ph.D. in Religious Studies in 1998, my work has more and more involved integrating knowledge and techniques from the sciences into the disciplines in which I was trained – early Chinese studies, philosophy, and religious studies. I’ve long argued that the early Confucian and Daoist models of personal perfection – a state of wú wéi (无为) or “effortless action,” where you act in a completely spontaneous but perfectly efficacious manner – make a lot of sense from a modern psychological perspective. Since I arrived at UBC in 2005, I’ve also been hanging out primarily with social psychologists and cognitive scientists and seen how a lot of phenomena they are “discovering” are actually things the Chinese have been talking about for a long time. So connecting the two pieces seemed like an obvious move to me.

What else did you learn while researching the book?

As far back as my dissertation in 1998, I’ve been arguing that the development of early Chinese thought was driven by a need to respond to a central tension, the paradox of wú wéi, or the problem of how you can try not to try. When I began focusing more on this issue from a modern psychological perspective in preparation for writing this book, I was surprised to find that this was a well-known and widely-studied paradox in social psychology and sports psychology, manifested in phenomena such as the challenge of suppressing unwanted thoughts or avoiding “choking” under pressure. So there was a rich body of empirical work to explore and share with readers.

How did you get involved in Asian studies in the first place, and in particular what sparked your interest in Chinese thought?

I was originally a science major as an undergrad at Princeton, initially studying molecular biology and then marine ecology. I had read a lot of Chinese philosophy in translation though, particularly early Daoist texts, and decided to take Chinese as well to satisfy my language requirement. I gradually discovered that I enjoyed the Chinese classes, and my classes on literature and philosophy, more than the science ones. I also had a bit of an early mid-life crisis at age 20 where I decided to leave the East Coast and ride my motorcycle across the country, eventually ending up in San Francisco and transferring to Stanford and switching my major to Chinese. I was reading a lot of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Jack Kerouac at the time, I think the character “Jaffy” in Dharma Bums – modeled on the poet Gary Snyder – had an impact. He was a grad student in Chinese and Japanese at Berkeley and spent his time sitting in the mountains reading haikus and drinking wine and I thought: "That sounds like a job that would suit me just fine."

Anything else you’d like to add?

One reason for this visit to Beijing is the launch of the Chinese translation of Trying Not to Try, which I am really glad has finally come out. It’s ironic that the country that originated the concept of wú wéi or “effortless action” is now probably the least wú wéi place on the planet. I think bringing back a little ancient Chinese philosophy to modern China could be a very helpful thing.

Slingerland will be talking at the Bookworm on Jan 10 at 7.30pm. Tickets are RMB 50. For more information, click here.

More stories by this author here.

Email: kylemullin@truerun.com

Twitter: @MulKyle

Instagram: mullin.kyle

Photos: thoughtco.com, Ted X, Penguin Randomhouse, Penguin