Beicology: What’s the Deal With Beijing’s Wacky Weather?

Recently, it seems Beijing really has been going through it, weatherwise. Dust storms and temperature drops. Snow and hail. Wind, wind, and more wind! WeChat updates constantly, throwing out alerts and warnings for what feels like every kind of weather under the sun. Disaster weather! The strongest winds in 70 years! And so on.

What gives?

Read on for a brief look into what's behind Beijing's wacky weather.

Beijing Topography and Climate

As we all most likely know, Beijing is in a kind of topographical bowl, with the Yan Mountains to the northeast and the Jundu Mountains and Western Hills to the northwest and cutting down along the city’s west side. The south and east of the city are open to the very large (and very flat) North China Plain, and a bit further southeast, past the plain, lies the Bohai Sea. Further to the west lies the Gobi Desert, and to the west and north of Beijing’s mountains lies the Mongolian Plateau.

This topography contributes to the regular patterns we are all familiar with. The surrounding mountains trap pollution in the "bowl" until it is blown away by northerly and northwesterly winds. Dust storms are common in April and May. January is the coldest month, and July and August are the hottest months.

Beijing has a mixed semi-arid, continental monsoon climate. Winters are dry and summers are humid. Beginning in October and lasting until March, cold, dry winds from Siberia sweep down over the Mongolian Plateau, through the mountains, and into Beijing, although the "bowl" effect mean that the city generally remains warmer than surrounding areas, the predominantly northwesterly air circulation of the area strongly negates any oceanic climate aspects which might be expected given Beijing’s proximity to the Bohai. In summer, hot and humid air pours into the city from the southeast. Summer is when Beijing sees most of its precipitation, although the amount varies from year to year.

Spring and fall are the most pleasant seasons, although they are short. Fall is clear and beautiful. Spring is nice as well, although it also is the windiest season, and is known for the aforementioned dust storms.

April Wind Event

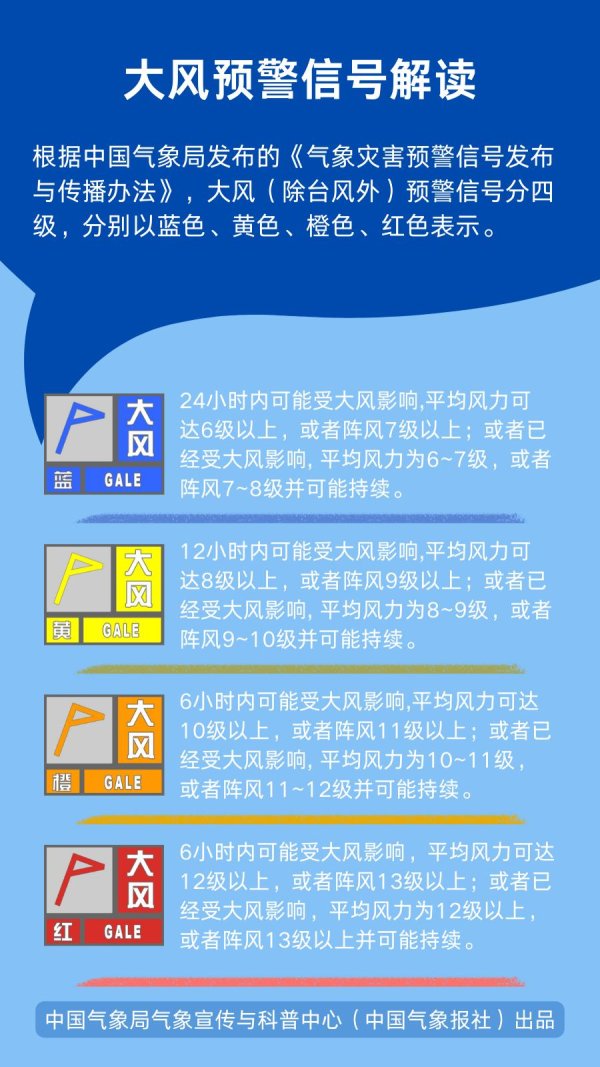

The recent mid-April wind event was due to a cold vortex that pushed in from Mongolia. The city issued its first ever orange level gale alert for strong winds and high-speed gusts. The city also witnessed sharp drops in temperature. On China’s wind speed scale, which goes from level 1 (the weakest) to level 17 (the strongest), the wind gusts caused by the cold vortex were predicted to be between levels 11 and 13, with outer districts seeing the highest level winds.

What’s a Cold Vortex?

A cold vortex shares some features with a polar vortex, but the two are not the same. A cold vortex is a low-pressure system that causes temperature drops, often with an increase in precipitation, that is smaller, lower, and more variable than a polar vortex. A cold vortex usually affects a specific area and is temporary.

Spring, being a transitional period in Beijing's seasonal cycle, already brings a bit of a mixture of weather phenomena. The addition of April's cold vortex event exacerbated the usual conditions, turning the expected spring weather mix into something more akin to a meteorological chaos stew.

Okay, But…Why. So. Windy?!

Well, it’s all down to something called the narrow tube effect, which is when wind velocity increases as the air flows through a constricted space. For Beijing, the same mountain passes that guaranteed the location’s historical importance in trade and communication routes between the North China Plain and areas on the other side of the mountains, including the Mongolian Plateau, act as the constricted spaces that greatly increase wind speed. This is also why warnings were more severe for northern and western outer districts – they are closer to, or located in, the mountains.

"Narrow tube effect." Pull that one out at parties – you’ll be a star.

China Weather Warnings

China uses four-color tiered warning systems for a range of weather events. While the details of weather conditions required to trigger each tier depend on the weather phenomenon in question, the warning colors are the same. In order from most to least severe, they are red, orange, yellow, and blue. This April’s orange gale alert was the second most severe warning for gale events.

Upon reflection, China’s weather alert systems use basically the same colors and ordering as the much-mocked Bush-era US Homeland Security Advisory System – it’s just poor, low-risk green that was given the boot. More than twenty years on from the establishment of that terror alert system, though, I think I can say that China’s weather alert system makes a lot more sense.

READ: Ten Tips for Secondhand App Shopping Success

Images: Pexels, Wikipedia/Seasonsinthesun (used under CC BY-SA 4.0 license), China Meteorological Association