Having grown up in Hong Kong, I can tell you from my own personal language learning experience that traditional characters (繁体字) are indeed an "impediment to literacy." Yes, traditionalists have a point in that "the simplification process has stripped the language of its beauty," however, I believe the point of a language -- any language for that matter -- is to convey a message clearly and concisely. Traditional characters just don't do that, they are overly complex. For example, take the word "learn": 学 and 學, in simplified and traditional form respectively; notice how completely unnecessary the upper-portion of the traditional character is. Sure, if you look at the etymology of the character, perhaps that upper-portion is supposed imitate the academic headgear a Chinese scholar would wear, but I believe such trivialities ruin the pragmatism of the Chinese language.

Simplified Chinese Characters Celebrate 60th Anniversary

Still controversial 60 years their adoption, native and non-native learners of written Chinese may have reason to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the adoption of simplified Chinese characters (简体字, jian ti zi)

As pointed out by Jottings from The Granite Studio blog's Jeremiah Jenne, China's State Council approved the first character simplification move on January 31, 1956. They have been used as the standard Chinese script in the People's Republic of China ever since, and have also seen some adoption in Japan and Singapore.

With traditional characters (繁体字, fan ti zi) seen as an impediment to literacy, the adoption of official simplified characters was also intended to create a standardized list of character simplifications, as non-standard variants of commonly-used by complex characters were frequently used.

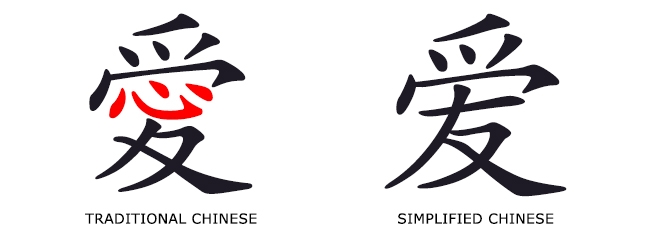

Traditionalists believe that the simplification process has stripped the language of its beauty, and in some cases, has devalued the meaning of words by replacing the complex, phonetic component of a character with a meaningless homonym. Another example is the character for 爱 (ai), love, in which the character for "heart," contained in the traditional character, was removed.

Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and many overseas Chinese continue to use traditional characters for both official and unofficial documents.

More stories by this author here.

Email: stevenschwankert@thebeijinger.com

Twitter: @greatwriteshark

Weibo: @SinoScuba潜水

Photo: Mosaic Taiwan