Pollution in China: A Doctor's Perspective

This post, in which International SOS's Dr. Michael Couturie provides advice for minimizing short and long-term health effects of pollution, comes courtesy of our content partners at AmCham China.

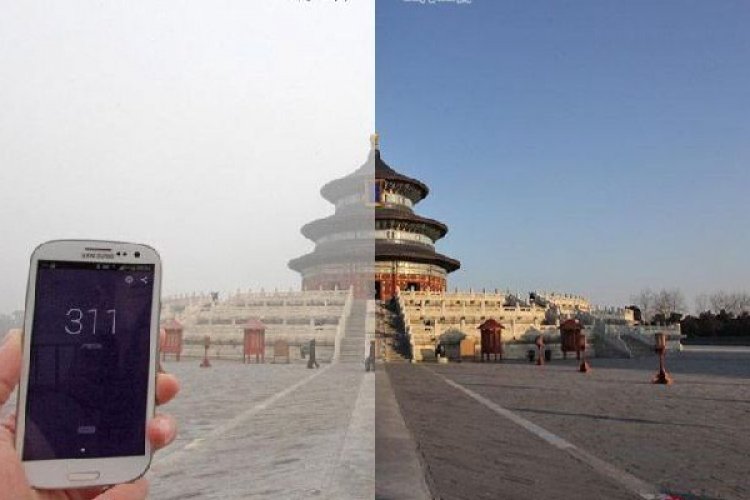

The same week as the Paris Climate Conference in November 2015, Beijing issued its first ever air quality Red Alert, causing schools to close and car use to be restricted. Just weeks before, the AQI had gone off the charts, the air so choked with haze that visibility decreased to less than 200 meters. For many of us who have been living in Beijing for several years, it was a rude reminder that while 2015 had been one of the best years in recent memory in terms of air quality, Beijing – indeed all of China – has many years of work ahead of it.

Of course, while it will take time for improvements to be made, people still need to live and work here. As a physician who sees quite a few expats living and working in Beijing, I am often asked what the health risks are, and what can be done to mitigate them.

RELATED: Beijing Dad's Air Quality Device Kicks off Crowdfunding Campaign

When health professionals think about air pollution’s health effects, we categorize them as short and long-term risks. In the short-term, for most people, the effects are limited to what you would expect: irritation in the respiratory tract and eyes, headaches, sometimes nausea. For those with asthma or heart conditions, or for the very young and very old, the short-term effects can be more severe and include asthma attacks, increased risk of infections and increased rates of cardiovascular events, and strokes in particular. In fact, my patients tend to concentrate on the air pollutants’ effects on the lungs, while many more people die of cardiovascular disease linked to increased air pollution levels. On the other hand, the long-term risks do, in fact, include lung cancer, which the World Health Organization only recently said was caused by outdoor air pollution, similar to secondhand smoke exposure. For children, we know from studies done in the US that growing up in an area with heavy air pollution levels will mean smaller lung volumes versus those who grow up in non-polluted environments.

There are, of course, some common sense steps one can take to minimize both the short and long-term air pollutions risks. On days when the AQI is elevated (above 100 for sensitive groups, 150 for everyone else), wearing a mask is appropriate. Masks are useless if not worn, and if not N95-certified don’t do anything significant with regards to pollution exposure reduction. The cute cotton masks one sees on the streets are useless. As important or more is mask fit. If the seal against the face isn’t tight, you just aren’t protected. And like most things that have to do with health, fancier and more expensive does not mean better: I use the 3M N95 mask, which is cheap and effective for reducing particle exposure. People should also limit the amount of outdoor activity they do during the most polluted portions of the day, which is usually dawn to dusk.

Finally, air purifiers do, in fact, remove particulate matter from the air. Given that 85 percent of most people’s time is spent indoors, air purifiers make a lot of sense, and these should be used indoors in the home and in the office. There is no data to show that the removal of particulate matter via air purifiers leads to better health outcomes, but there’s no reason to suspect it won’t.

Organizations that bring people to China have a role to play, too. Deciding to move and possibly bring a family to a place where exposure to outdoor air can be a health risk should not be an easy decision. Organizations should take seriously their duty to care for their staff: providing air purifiers in the office, providing masks and being flexible with working on high AQI days are all appropriate steps to take. (Editor's note: Read more advice on how companies can ensure safe indoor air quality.)

Nevertheless, it’s also important to keep relative health risks in perspective. It makes little sense for a person who smokes to worry about pollution. Not exercising out of fear of being outside will probably have a bigger impact on long-term health than occasional exposures. An unhealthy diet over a lifetime is almost certainly a bigger health risk than intermittent exposure to air pollution. I encourage my patients to take reasonable precautions such as masks and air purifiers, but to not lose sight of the daily diet and exercise habits that will have a much bigger role in their long-term health.

Dr. Michael Couturie is a Family Doctor, Internal Medicine Specialist at International SOS, an AmCham China member company. Couturie completed his residency (as Chief Resident) in Philadelphia, and subsequently worked as a hospitalist in various hospitals in the region, including Abington Memorial Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Temple University Hospital and Fox Chase Cancer Centre. Couturie then worked with Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders in the Central African Republic, Haiti and Zambia for three years. He has been living and working in Beijing since 2012. He received his M.D. at the Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University.

Photo: money.pl