Historic Courtyards and Residences That Could (or Should) Be Opened to the Public

Have you ever walked down a hutong past a grand gate and stopped to wonder just what was hidden behind those high brick walls? You might not have to wonder for much longer if Cai Qi, Communist Party Secretary for Beijing has his way.

Beijing should work harder to preserve its ancient courtyards and the residences of historical figures, Secretary Cai announced at last week’s inaugural meeting of something called the National Cultural Center Construction Leading Group. After all, nothing says, “We’re committed to preserving the organic culture and past of a city” like turning that job over to a cabal of government functionaries.

In any case, to the extent that the Municipal Government ever listens to our suggestions, if Secretary Cai is serious then we have a few spaces worth considering:

Keyuan

Long considered one of Beijing’s best-preserved gardens, this Qing-era residence occupies the space between #7 and #13 on Mao’er Hutong just to the west of Nanluogu Xiang. Its imperial occupant built his garden with lavish attention, constructing a fairyland of rocks, water, paths, trees, and buildings. Unfortunately, for most of the past six decades, Keyuan has been the property of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The site has long been a point of concern for preservationists. A proposed project in 2008 to demolish a portion of the garden drew an impassioned response from the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center (CHP). Then Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Qin Gang, in response to a reporter’s question, said that Keyuan was to be restored and opened to the public. That was in 2008.

Locked and sealed, viewed only occasionally by a lucky few, the magnificent garden remains off-limits.

Former Residence of Chiang Kai-shek

Not far away from Keyuan, on the other side of Nanluogu Xiang, is the former mansion of Zaibo, who was a member of a prominent family. (Dad was a prince and Zaibo was a great-great-grandson of the Qianlong Emperor [r. 1722-1796].) His garden, located at #7 along the north side of Hou Yuan’ensi Hutong, features a hodge-podge of East and West, with European-influenced-gates and domed structures alongside Chinese-style gardens and pavilions.

Zaibo would later gamble away the family homestead, and in the 20th century, the gardens became the Beijing headquarters for none other than Chiang Kai-shek, who took a fancy to the place. Chiang would use the garden to host meetings with his generals and other Beijing notables. Like Keyuan, these gardens are also currently under the control of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and at one point after the revolution, the gardens served as the Embassy of Yugoslavia. Also like Keyuan, these gardens are currently closed to the public. Peeks inside through open doors reveal a lot of construction work and renovations being done to some of the historic structures. Unfortunately, an answer about the future of the garden was not forthcoming from the young uniformed gentleman minding the gate.

Former Residence of Prince Chun

This one's a doozy, both in physical scale and in recounting its historical ownership:

Taking up nearly one-third of the northern shore of Houhai, this massive garden was once the home of the Zaifeng, also known as Prince Chun, and the birthplace of Zaifeng’s son – the last emperor of the Qing Empire, Puyi. Originally constructed by the Manchu official Mingju (1635-1708), this magnificent estate went through a succession of owners during the Qing era.

Mingju was a favorite of the Kangxi Emperor [r. 1662-1722] and was given permission to build his palatial home, including sweeping gardens and even an irrigation system. Mingju fell from power in 1688 but the mansion stayed in the family until the end of the 18th century, when the corrupt official Heshen (who was rumored to have had a “very special relationship” with the Qianlong Emperor) seized the gardens for his own use.

Heshen’s reign of avarice came to an abrupt end with the death of the Qianlong Emperor in 1799, and the garden passed to a succession of imperial relatives until it wound up being the home of Yixuan, the first Prince Chun, in 1888. His son Zaifeng inherited the mansion and his father’s title in 1891. Zaifeng and his descendants (not including Puyi) lived here until the revolution in 1949, but the estate soon fell into disrepair and ruin.

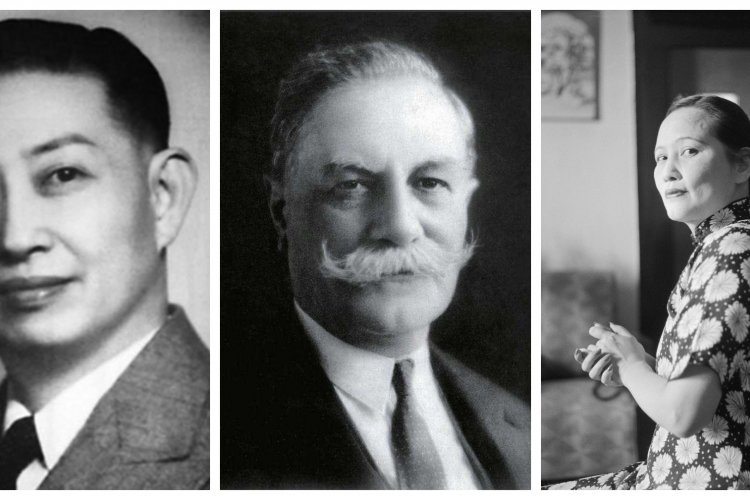

The new government confiscated the property and eventually divided it into two sections: The Western gardens became the home of Soong Ch’ing-ling, the widow of Sun Yat-sen, who lived there from 1959 until her death in 1980, and are now open to the public; the Eastern residential palaces were converted into state offices and have been, with a few brief exceptional periods (the last being in 2006), closed to the public. At present, the Eastern section houses the office of the State Religious Affairs Bureau.

Photos: Wikipedia, Sino-US.com, Beijing Tourism

Jeremiah Jenne is a historian, writer, and educator based in Beijing since 2002. Jeremiah is also the proprietor of Beijing by Foot, which organizes educational programs and historic walks in Beijing.