Beijing Lights: Life Is Like Gambling

This post is part of an ongoing series by the Spittoon Collective that aims to share some of the voices that make up Beijing’s 21.7 million humans. They ask: Who are these people we pass in the street every day? Who lives behind those endless walls of apartment windows? These interviews take a small, but meaningful look.

Note from the author: I like to think that every small neighborhood shop is a station brimming with information about that community. Fragments of stories are constantly being told—and getting lost just as quickly. The housewife who drops in every now and then to restock on grains and spices for her family, the elders who live alone, the young man who comes in for several bottles of cheap Yanjing beer—they all leave a mark as clear as what is in the shop’s account books. The shop owner, even without intending to, is the primary witness recording these forgotten stories.

Zhou Hongyan is such a shop owner, transmitting the stories of her customers every time I visit. At the end of our conversations, she often sighs, adding, “No one’s life is easy.” As for her own life, the details leaked through here and there as she talked about others, as if her own experiences were no different than the trivial gossip of other families.

Zhou Hongyan, female, 48 years old, from Henan, small shop owner

The cause of most of the suffering I’ve had in my life was that I’m a woman.

The hardships that a woman experiences, as a kid I saw them all in my mom’s life. I was born in July, the season for transplanting rice seedlings. As soon as my mom gave birth, she was out in the fields again working. That kind of heavy labor on the farm gave rise to a lifetime of health issues.

I was born with one elder brother and four elder sisters. My dad was patriarchal, favoring boys over girls. He never showed me much affection. He worked in a town cooperative and barely came home, leaving all the household chores to my mom and us sisters. Before I turned ten, I was helping with cleaning, cooking, and feeding the pigs.

Because I was a girl, I didn’t get as much education as I wanted. By my early teens I was out looking for jobs. I started as a babysitter in Beijing. The pay was only 40 kuai per month. After half a year, they wouldn’t raise it to more than 65, so I quit and found work serving food in a Korean restaurant.

Back then, there were many boys chasing me. Not to sing my own praise but I was a good-looking young lady. My skin was fair and rosy, and I didn’t need to wear makeup.

Without any wedding ceremony, I married my husband at 19. He is plain-looking, thin, not even very tall. I was only drawn to his kindness and generosity.

As soon as we got married, the sweetness of our relationship was immediately swallowed by the roughness of life. We started a small restaurant in our hometown. It was a lot of hard work. I was getting up early and staying up late, cutting vegetables, scrubbing pots, washing the dishes. It didn’t matter how cold the winter got, my hands soaked in the freezing water all day until they were red and swollen.

But that hardship is hardly worth mentioning compared to what I experienced later in my life.

I’ve gotten pregnant and then suffered miscarriages—the utmost pain a woman can experience—a dozen times. Each time it felt like my skin was being peeled off.

The first time I got pregnant, my husband and I weren’t married yet. So I had an abortion. My second pregnancy I carried to term, but when I was giving birth the baby died inside me from malposition. The doctor had to remove the baby from my stomach little by little. I laid on the operating table for a full day and night. I almost died on that table.

It wasn’t long until I got pregnant a third time. But when the baby was seven months old, I had a miscarriage. After three failed pregnancies, I couldn’t bear the pain of another attempt. One night, I got up from bed and snuck outside. I wanted to escape from my life. But before I could get far, I was caught and dragged back home. To frighten me from trying again, my husband lashed me with his belt until there were black and purple bruises covering my whole body.

I tried to run away a few more times and finally succeeded. I managed to arrive in Beijing and stayed with one of my sisters. About three months later, my husband found me and begged to stay.

In Beijing I eventually had a successful pregnancy and gave birth to our son. When he was three months old, I sent him back to be raised by his grandparents. I was too busy with work to take good care of him.

After my son, I got pregnant again several more times. But none of the babies survived. Some were ectopic, some were miscarriages. There’s always some problem. With one of them I knew I was carrying a baby girl, and I wanted to keep her. But it was another miscarriage. She would have been a teenager by now.

I don’t like to think about the past often. As for my grievances, I can’t talk about them with my husband, and I rarely chat with my son either. Since my mother passed away, I have never returned home. Sometimes I want to visit her grave and talk to her, but I can’t. Because according to the village’s rules, married daughters are not allowed to visit the graves of their ancestors.

Fate is a strange thing. You never know. Out of all those boys who wanted to be with me, I picked my husband. Some of life’s biggest choices end up being just like gambling. Few people get to call themselves a winner.

Edited by Dan Xin Huang

READ: Beijing Lights: Every Day a New Yearning for Life

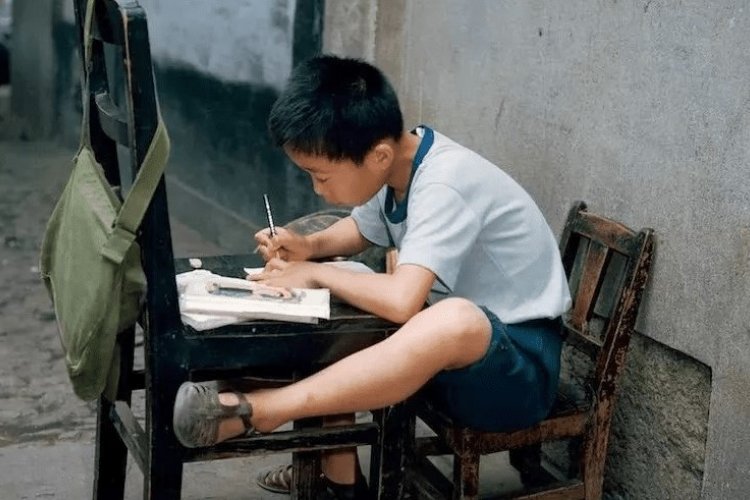

Image: Huang Chenkuang