Red-Letter Day: Uncovering Beijing’s Literary and Ideological Past

It’s a bitterly cold Beijing morning with flurries of snow floating around us. I’m joining Nelly Alix from Beijing by Heart (who also took us on a visit of Guozijian last August) for a three-hour walking tour. We’ll be exploring the city’s past, with stops at the former residence of writer Lao She, the Red Building of the old Peking University, and Zhongshan Park, where writers gathered for artistic inspiration in the 1920s.

We begin the tour at Dengshikou (subway line 5, exit A) in Dongcheng District. Dengshikou got its name from the lantern market that used to take place here in the first month of the Chinese lunar year. The market was moved to the outer city in the Qing Dynasty, but the name remained.

We walk west on Baishu Hutong (柏树胡同), winding our way along the narrow lane. The term “hutong” originates from the Mongolian word for “well,” hottog. In ancient times, villagers would dig up a well and live around it. Constructed according to the rules of feng shui, residential hutongs run east to west, with the main entrance facing south to let in the sun in winter and the breeze in summer. The hutongs in Dongcheng are among the most extensive and best-preserved in Beijing.

We arrive at the Church of St. Joseph (大若瑟堂), built in the 17th century by Italian missionaries. One of the oldest Christian churches in Beijing, the building was completely destroyed during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. It was rebuilt in 1904 in the Baroque style, which was particularly popular in the Jesuit community. Today, St. Joseph’s is known as Dong Tang or East Cathedral. English and Chinese language services as well as wedding ceremonies are regularly held here.

After a brief respite from the cold, we cross the church square towards one of Beijing’s most famous streets, Wangfujing Dajie (王府井大街). The name Wangfujing means “prince’s well,” named after a well that was said not to run dry during droughts and used to give water to the locals. When Beijing was still a city with dusty streets in the 1920s, Wangfujing Dajie was paved and modernization began.

We head west towards Fengfu Hutong (丰富胡同). Alix describes life in Beijing after the Qing Dynasty fell in 1912. “Beijing went through an identity crisis,” she says. “It marked the end of thousands of years of powerful imperial rule, and in theory was the start of a new era in which political power rested with the people.”

At the time, China was a fragmented nation dominated by warlords who were more concerned with their own political power than national interests. During the period that followed, life in Beijing slowed considerably, a marked difference from the upheavals taking place in Shanghai. Writers and artists flourished – among them was Lao She.

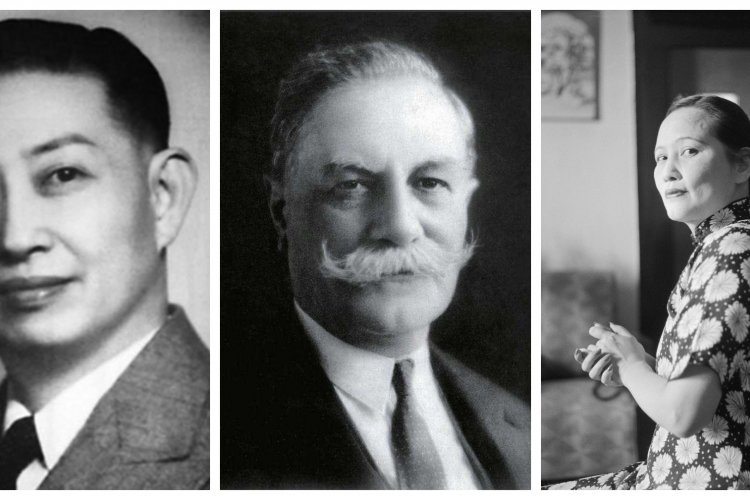

Lao She (1899-1966) was the pen name of Shu Qingchun, Beijing’s most beloved novelist and dramatist. He was one of the most significant figures of 20th century Chinese literature, best known for his novel Rickshaw Boy and the play Teahouse. Of Manchu descent, his works are renowned for their vivid use of Beijing dialect. His former residence is now a museum known as the Lao She Memorial. The writer lived in this courtyard home from 1950 up until his death 16 years later. It contains the author’s library and living quarters, including a writing desk with his daily calendar still open to the date of his death in August 1966. The persimmon trees, planted with his wife in the courtyard, still stand today.

Between 1918 and 1924, Lao She taught in Beijing and was deeply influenced by the May Fourth Movement of 1919. While a lecturer at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, he also absorbed a great deal of English literature. “He loved the works of Dickens,” says Alix. “Dickens wrote about ordinary folk in a dry and quite satirical style. This inspired Lao She to write about the ordinary people of Beijing.”

Lao She also traveled to the US, lecturing and overseeing the translation of several of his novels. Like thousands of other intellectuals, he was persecuted during the Cultural Revolution. Humiliated by his treatment at the hands of the Red Guards, he committed suicide by drowning himself in Beijing’s Taiping Lake. His wife, the calligrapher Hu Jieqing, survived him along with their son and three daughters.

We exit the museum, walk west to Beiheyan Dajie (北河沿大街), and continue north. Despite the cold, a group of pensioners are playing chess outside. On the same street is Bicycle Kingdom, a popular bike rental company. According to Alix, the bikes are well-maintained and rental prices are reasonable.

On the northwest intersection of Beiheyan Dajie and Wusi Dajie (五四大街) or “May Fourth Street,” a four-story red brick building sits among newer office structures. Its rather plain appearance belies its significance in Chinese history. Eighty-three years ago, the May Fourth Movement (Wǔsì Yùndòng) began here. This anti-imperialist and political movement grew out of student demonstrations that took place in Beijing on May 4, 1919.

Protesting the Chinese government’s weak response to the Treaty of Versailles, the demonstrations sparked the New Culture Movement and an upsurge in Chinese nationalism. “People began to break away from the limits of Confucianism and accept Darwinism and other Western philosophies,” says Alix.

Formerly a Peking University campus, the Red Building (Honglou) is now the New Culture Movement Museum of China. We peer into the room where Mao worked as a library assistant when he first came to Beijing in 1918. It was during that time that Mao developed a stronger interest in Marxism. “He was exposed to the ideas of Dean Chen Duxiu and Librarian Li Dazhao, who later became founders of the Chinese Communist Party” says Alix.

We also stop by the room where writer Lu Xun gave lectures. He wrote the short story “A Madman’s Diary,” one of the most famous pieces of modern Chinese writing. Also on display at the museum is the first edition of La Jeunesse, a Chinese magazine that played a crucial role in the New Culture Movement. Many of the young lecturers contributed to the magazine, which promoted science, democracy, vernacular (báihuà), Chinese literature, and Marxist philosophy.

We now enter a section of the museum that documents the activities of May 4. “Over 3,000 students marched that afternoon to gather in front of Tian’anmen. They voiced their anger at the Allied betrayal of China,” says Alix. “In its broader sense, the May Fourth Movement led to the establishment of radical intellectuals.” These intellectuals went on to mobilize peasants and workers, bringing them into the Communist Party and giving the party the strength it needed for the Cultural Revolution.

We leave the museum and head west on Wusi Dajie. At the junction of Wusi Dajie and Beichizi is Oasis Café, which serves great pizzas and even better hot chocolate, making it the ideal place for a break. To our right in the distance, we can see Jingshan Hill within Jingshan Park (景山公园), an artificial hill dating from the early Ming Empire and built with the the soil excavated from the moat surrounding the Forbidden City. Families with younger kids may decide to end their tour at Jingshan Park, which has plenty of space to play in and a central pavilion with a great view of the city.

We stroll south on Beichizi (北池子), then Nanchizi (南池子) along the walkway that encircles the perimeter wall, guard towers, and 52m-wide moat of the Forbidden City, which remain intact.

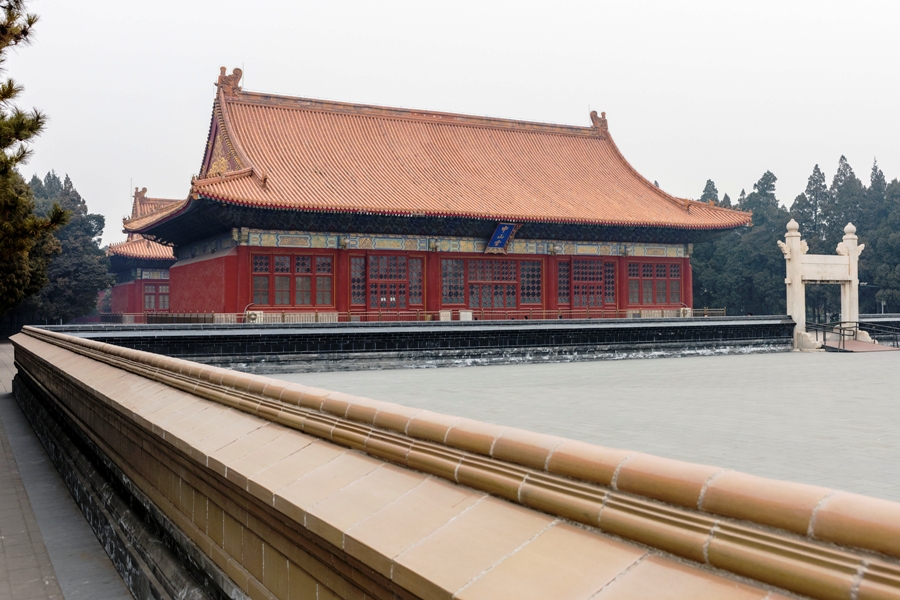

Zhongshan Park (中山公元) is a former imperial garden that sits just southwest of the Forbidden City. Popular among literary folk during the 1920s, the park boasts some of the oldest trees in Beijing, including 800-year-old cypresses and junipers. Regulars include the elderly who show up here on Thursday mornings, brandishing leaflets advertising the good qualities of their unmarried offspring.

Zhongshan Park houses numerous pavilions, teahouses, and temples. The pavilions are truly beautiful, with the distinctive glazed yellow roof tiles reserved for imperial buildings. “When the last dynasty fell, Beijing was a place of great poverty. So many workshops and their people had relied upon the Forbidden City and everything that it represented,” explains Alix, referring to the artisans who made every brick and tile. After the abdication of Puyi, the last Emperor of China, he retained the use of the Inner Court while the Outer Court was handed over to the Republican authorities and opened up to the public.

Beijing by Heart offers tours in English and French. The history walks are suitable for small groups of no more than eight people and cost RMB 300 per person (RMB 150 for ages 8-16). Private tours are also available. Other tours include In the Heart of the Hutongs and The History of the Opium Wars. Email info@beijingbyheart.com or visit www.beijingbyheart.com.

Stops

Dong Tang (East Cathedral) 东堂

74 Wangfujing Dajie, Dongcheng District (6524 0634)

东城区王府井大街74号

Lao She Memorial 老舍故居

Tue-Sun 9am-4.30pm. 19 Fengfu Hutong, Dongcheng District (6559 9218, laoshe1899@126.com) www.bjlsjng.com

东城区灯市口西街丰富胡同19号

Bicycle Kingdom 康多自行车店

Daily 9am-6pm (Feb-Dec). 81 Beiheyan Dajie, Dongcheng District (6526 5857, info@bikebeijing.com) www.bikebeijing.com

东城区北河沿大街81号

New Culture Movement Memorial Museum 新文化运动纪念馆

Tue-Sun 8.30am-4.30pm. 29 Wusi Dajie, Dongcheng District (6402 4929)

东城区五四大街29号

Oasis Café

1 Jingshan Qianjie, Dongcheng District (186 0115 0266)

东城区景山前街1号

Jingshan Park 景山公园

RMB 10. Daily 6.30am-9pm. 44 Jingshan Xijie, Xicheng District (6403 8098)

西城区景山西街44号

Zhongshan Park 中山公园

RMB 5. Open 6am-9pm (summer), 6.30am-8pm (winter). 4 Zhonghua Lu (southwest of the Forbidden City), Dongcheng District (6605 5431)

东城区中华路4号(天安门西南侧)

This article originally appeared on our sister site beijingkids in March 2015.

Photos: Sui