The Awkward Position of Missionaries: Religion and Violence in 19th-Century China

This guest post comes our way via Beijing-based writer and historian Jeremiah Jenne (Jottings from the Granite Studio), who presents Hacked History: The Awkward Position of Missionaries this weekend at The Hutong.

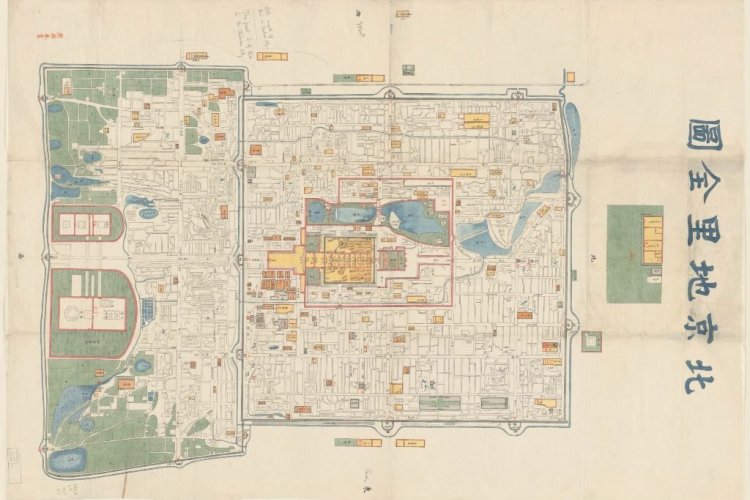

In the summer of 1870, Tianjin was in a panic. Rumors of sorcery, child abductions, and murder ran through the city. Suspicious minds turned to a new presence in their midst: the Catholic mission and orphanage just outside the east gate of the city. The nuns there took in so many children, and so few ever came out again. Meanwhile, the Catholic cemetery filled with graves and bones.

Spooked city residents begged the local magistrate to investigate these crimes. But like many officials in 19th-century China, he was caught in the middle between foreign powers, who insisted on the rights of missionaries to spread the word of God in China, and local residents who feared and loathed the missions. Side with their constituents and risk starting a war. Protect the missionaries and risk being strung up with them.

How did this ever happen? On March 27 I will give a talk and discussion at The Hutong about that fateful summer of 1870 and missionaries in old China, ther result of spending several years researching the events in Tianjin, dug up from the Imperial Archives in Beijing as well as archives in France and the United States.

The drama that unfolded in Tianjin that summer featured a cast of colorful characters. In addition to our hapless magistrate and angry residents, there was a hot-headed French consul who vowed to protect the dignity of the church at all costs. There were local ruffians, the old Tianjin equivalent of Hell’s Angels, who vowed to protect their turf by doing whatever it took. And then there was Chonghou, a Manchu functionary in charge of trade in the city, whom The Economist magazine once branded China’s worst diplomat ever.

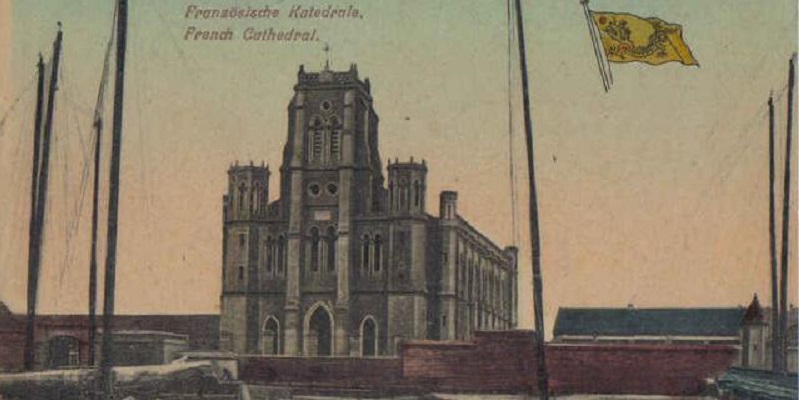

The result was a day of rage and violence that shocked the world and left China and France on the brink of war. Over 21 foreign residents, including 16 nuns, were brutally killed and the French cathedral and orphanage burned to the ground.

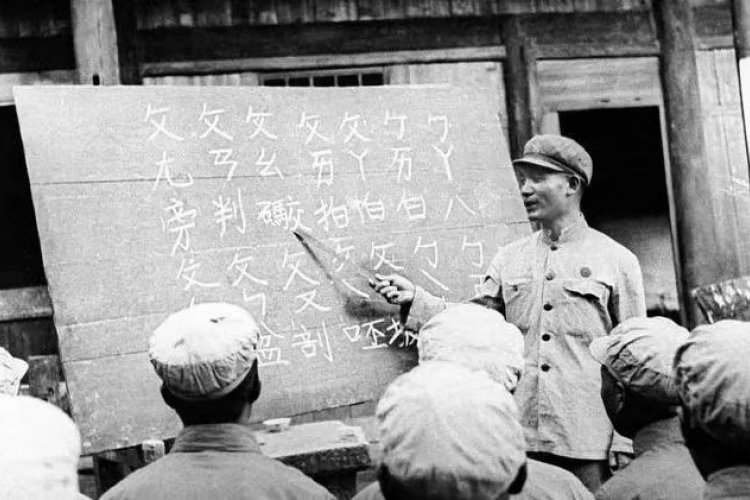

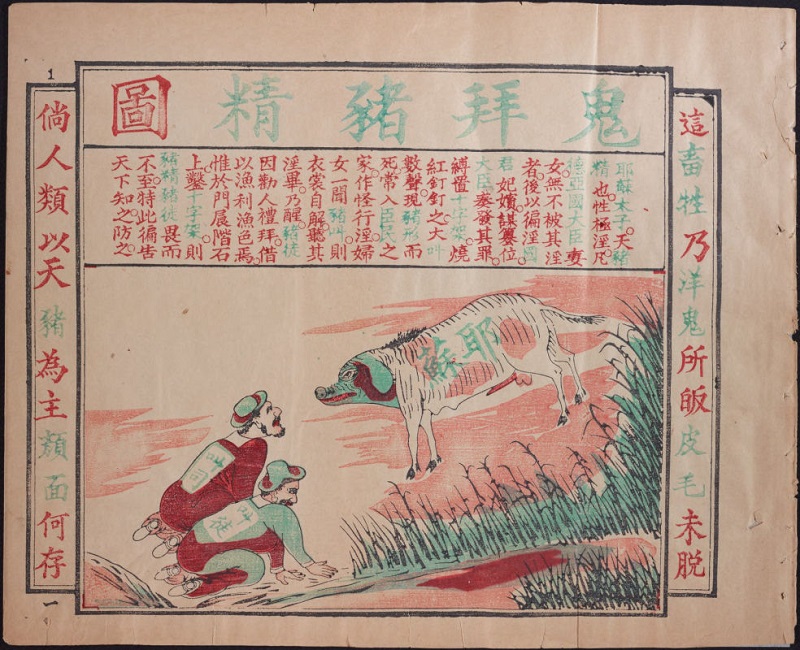

What became known as the Tianjin Massacre was the culmination of nearly a decade of anti-missionary activity in China. In 1860, a new set of treaties between the Qing government and the foreign powers gave missionaries unprecedented rights to travel, preach, and build churches in the interior of China. Foreign missionaries saw themselves as doing God’s work, but for many local residents and officials they were the most obtrusive and obvious examples of foreign power and privilege. Anti-Christian pamphlets began appearing throughout the country that claimed that Christianity was a demonic practice where worshippers sacrificed a child, drank its blood and ate its flesh, before then copulating wildly on the floor of the church.

The missionaries, and many later historians, blamed the local elite for all of the trouble. Threatened by the missionaries’ new ideas and their immunity to local prosecution, the elites stirred up the rabble against the interlopers. Historians in China have long viewed anti-missionary activities as the patriotic spirit of the common people against foreign imperialism. As in many subjects related to China, the answer lies somewhere in between and is far more interesting.

Hear more about this pivotal incident in Chinese/Foreign relations Sunday (Mar 27) at Jenne's lecture and discussion Hacked History: The Awkward Position of Missionaries at The Hutong from 2-3.30pm (RMB 50 / RMB 40 The Hutong members).

Images: Jeremiah Jenne