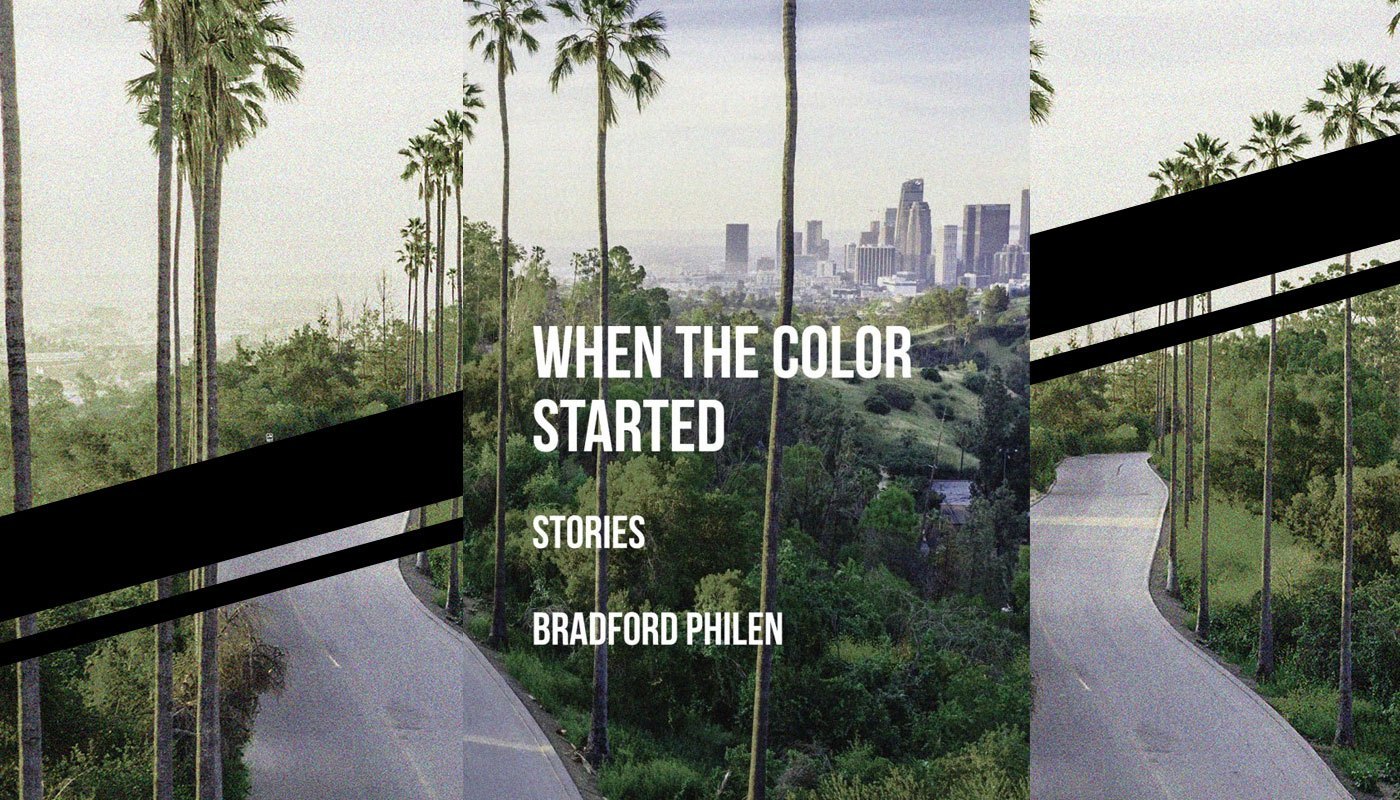

When the Color Started: Examining the Short Stories of Formerly Beijing-Based Bradford Philen

This review originally appeared on the Spittoon website. Spittoon is a Beijing-based arts collective that does events and programming throughout China and publishes a literary magazine and a comic book, all with the goal of bringing together Chinese and foreign writers, artists, and literary enthusiasts.

“I don’t hear God like that. I just feel him when he grabs my throat.” So says a limo driver inexplicably mistaken by a wealthy passenger for her husband. What does it mean to be recognized? This is the question I am left with after reading Bradford Philen’s collection of short stories, When the Color Started. In this collection, Brad betrays a profound sense of character. But character, as he shows us, is anything but a straightforward concept in the 21st century.

Indeed, I am reminded of reading this collection that each of us is an answer. We are each an answer to the question, who are you? But as we search ourselves for a referent to this who, we inevitably are left with many what’s. The typical reaction to this discrepancy is denial: I am more than my supposed identity, my labels.

“We’re all born with a lot of wild and crazy things going on around us,” says a mysterious drifter in “A Night at Ovell’s Casino.” This is true for many of the characters in this collection, for who identity is a constraint imposed by others, something against which the singular self must bristle until it breaks free. An American Muay Thai fighter in Thailand reckons with his relationship to a foreign country and people; a young Black man finds himself caught between the world he came from and the Ivy Leagues, between conventional masculinity and his own singular desire; a middle-aged man committed to counseling for indecent exposure is pressed to answer the question: “Why do you think you’ve become the person you are today?”

This last story, “Normal Earl,” and another one, “Father Like Lion,” speak to men’s search for an estranged tenderness—one that men are too often taught to fear. In these stories, Philen teaches us something about identity. Identity is superficial and arbitrary, yes, but not worthless, not something to be simply discarded. Rather, it is in our struggle against identity that we find ourselves.

Color is thus an apt metaphor in this collection. Not only for race—which is at the center of many of these stories—but also for character in general. Color is an effect: an effect influenced by light and context, that which is underneath and surrounding it. In the titular story, a Black boy remembers his mother’s warning when child services knock on his door, “Son, you’re always going to be black first.” We see our identity in others’ gazes, those what’s that supposedly define us, but we are never satisfied with this. The boy offers the authorities some fruit from his basement, fruit which, in a surreal turn, makes them hallucinate and completely forget about the boy.

Identity is also a kind of magic. When it is given to us, it is meaningless—color in the dark; only when we come to realize its implications in the world does its meaning become clear. Nothing actually changes, the world just starts to look different. We start to look different to ourselves. This is often the animating force behind Philen's characters, that which drives them into themselves in search of answers.

“Sometimes the things you do, don’t tell the world who you really are,” says the main character of “Chosen.” Who we really are is at the center of this book. It cannot be reduced to a single identity, but it also cannot exist without the limitations identity imposes on us. Who I really am is the obvious answer to the question, who are you? But like color without light, without context, who I really am is meaningless. When the Color Started is not about finding who you are, it is about asking the question.

READ: On the Importance of Isolation With Beijing-Based Poet Zuo Fei

Image: Spittoon

Related stories :

Comments

New comments are displayed first.Comments

![]() Sikaote

Submitted by Guest on Sun, 11/01/2020 - 17:33 Permalink

Sikaote

Submitted by Guest on Sun, 11/01/2020 - 17:33 Permalink

Re: When the Color Started: Examining the Short Stories of...

We are each an answer to the question, who are you?

I am...not you.

Validate your mobile phone number to post comments.