Slow Boats and Caravans: Great Explorers in Chinese History

China was never closed to the world. The myth of Chinese civilization huddled behind the Great Wall, isolated and insular, is as much a product of Western imagination as any historical reality. For thousands of years, travelers, traders, scholars, and missionaries explored the overland routes and sea lanes connecting China with the rest of the world.

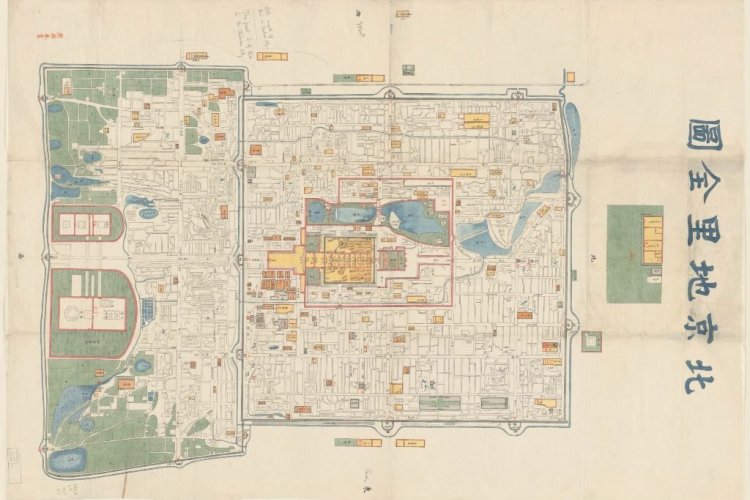

Perhaps best known is Marco Polo, who recorded an account of his long journey from Venice to Khanbaliq, today’s Beijing, in the late 13th century. Equally famous, at least in China, is Admiral Zheng He, who led a series of oceanic sorties throughout the Indian Ocean between 1405 and 1433, reaching the coastlines of the Arabian Peninsula and Eastern Africa. They were the best known but far from the only explorers to make the long voyage between East and West.

Zhang Qian (who died in 113BCE) served as an official and diplomat during the Han Era. He was one of the first Chinese officials to travel what would later be known as the Silk Road. At the time, the Han Empire was surrounded by hostile groups, notably the Xiongnu who controlled the steppes of today’s Mongolia. In 138BCE, Zhang Qian led a secret expedition right through the heart of the Xiongnu territories to make contact with the kingdoms of Central Asia and forge alliances against the Xiongnu. Zhang Qian’s mission hit something of a snag when he and his team were captured by Xiongnu. For 10 years, Zhang Qian served his captors as a slave before he could escape and return to China. Despite the setback, Zhang Qian brought back a wealth of information about the people and geography of Central Asia, intelligence which the Han Empire would use in their conquest and subjugation of Central Asia later.

Nearly two centuries after Zhang Qian’s return, Chinese general Ban Chao (32-102CE) retraced the route of Zhang Qian as Ban Chao sought to expand Han rule throughout the desert oases of today’s Xinjiang. By the end of the first century CE, Ban Chao had succeeded in pacifying all of the Western Regions and even sent an envoy Gan Ying on a mission to the court of the Roman Emperor. Gan Ying never made it to Rome (he got as far as the Black Sea), but Gan Ying did bring back accounts of Roman political life and culture. (The “Explorer General” IPA sold by Great Leap Brewery is named in honor of Ban Chao.)

Perhaps the most famous traveler to the West was the monk Xuanzang (c. 602-664CE). For 17 years, Xuanzang traveled across deserts and mountains on a quest to reach India. Along the way, he studied at many famous Buddhist monasteries, and returned to China with a treasure trove of Buddhist scripture. Xuanzang was not only one of history’s great travelers, but he was also one of the most influential translators of religious scripture in world history, translating over 1,000 texts from Sanskrit into Chinese. He is most famous in China though as the subject of the Ming-era fantasy novel Journey to the West written by Wu Cheng’en. Wu embellished the stories of Xuanzang’s voyages, adding a colorful cast of characters including the Monkey King Sun Wukong and the half- human half-pig Zhu Bajie.

Centuries before Marco Polo, travelers and traders from Eastern Europe and Western Asia made the perilous journey to reach China. Chang’an, the capital of the Tang Empire (618-907CE), was the cosmopolitan epicenter of pre-modern global trade. When the emergence of new steppe powers such as the Mongols threatened to cut off overland trade routes to China in the 12th century, the flow of goods and people took to the high seas. Sea routes connected the coastlines of Fujian and Guangdong with faraway ports in India and Western Asia.

The Mongol’s ultimate success in conquering most of the known world led to a brief period in the 13th and 14th centuries when traders could cross a Central Asia more or less unified by conquest. The break-up of the Mongolian Empire into competing successor states ended this period of “Pax Mongolica” and inspired many countries, including Ming-era China and the states of Western Europe, into a new age of exploration in the 15th century.

European ships began reaching the East coast of Asia in the early 16th century, and soon outposts of European trading empires began taking root from Macao to Malacca. These ships brought not only trade but also missionaries. Perhaps the most famous pioneer to reach Beijing in the post-Marco Polo era was another Italian, Matteo Ricci. Ricci was a Jesuit priest whose eidetic memory allowed him to master the Chinese Language quickly. In 1601, Ricci became the first European to enter the Forbidden City.

Ironically, the court was interested in employing Ricci and his fellow Jesuit not for their religion but their knowledge of astronomy and science. While in the service of the Wanli Emperor, Ricci translated Euclid’s Elements of Geometry into Chinese while also being one of the first scholars to introduce the Confucian classics to a European audience. Like Xuanzang nearly a millennium before, Ricci’s explorations were as much about crossing cultural and intellectual frontiers as much as actual physical space.

For thousands of years, people from all over the world have been coming and going along the roads and through the ports of what is today China. Not everyone became a religious and cultural phenomenon like Xuanzang, or was as prolific a translator as Matteo Ricci, or had a beer named after them like Ban Chao. But today’s Lao Wai and Hai Gui are part of a long and important tradition connecting China with the rest of the world.

This article first appeared in the March/April issue of the Beijinger.

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer, educator, and historian based in Beijing since 2002. He is also the founder of Beijing by Foot, which offers historical walks, tours, and workshops in Beijing and maintains the history, culture, and travel website Jottings from the Granite Studio. You can find him on Twitter @granitestudio.

Photo: confucius-angers.eu

Related stories :

Comments

New comments are displayed first.Comments

![]() schreursm

Submitted by Guest on Thu, 04/20/2017 - 14:48 Permalink

schreursm

Submitted by Guest on Thu, 04/20/2017 - 14:48 Permalink

Re: Slow Boats and Caravans: Great Explorers in Chinese History

since living in Beijing, I have been reading books to gain a better under standing of the chinese history. I applaud the author of this article. It covers more information than what I found in the many books that I read.

We will pass that on to the author, thanks for your feedback!

Validate your mobile phone number to post comments.